Peculiar strategical decisions made both in Japan and the United States prevented an active participation of the Japanese main fleet in the actions from the Solomons to the Marianas. Before we will discuss the Battle of the Philippine Sea, a look at those strategy decisions will be in order.

The Preliminaries: The Stage, February 1943 to May 1944 American Moves

The major Allied conferences of early 1943 had many important topics to discuss, among which, albeit at a lower priority, was the decision of which route to pursue in the defeat of Japan. Should the main U.S. thrust be along the line advocated by General Douglas MacArthur, the persuasive and grandiose commander of the South West Pacific area? Or should it follow the route of the old War Plan Orange, a Central Pacific campaign in which island bases would be secured until the Philippines were reached, as was argued by the tough and unforgiving Admiral Ernest J. King, Commander-in-Chief, U.S. Fleet and Chief of Naval Operations?

Long discussions followed, but King had a major advantage to MacArthur: he could argue his plan in person at every meeting of the Joint Chiefs of Staff, the high authority for U.S. strategy, where King was a member and MacArthur not. And, unlike MacArthur, he had something to offer to one of his colleagues on the JCS.

King’s plan aimed, among other things, at taking

the Marianas islands in the central Pacific, lying like a barrier across the direct route from Hawaii to the Philippines. Although the Pacific Fleet’s planners were lukewarm at best to the

idea (and had, in private conference with MacArthur’s command, preferred the southern approach), King’s idea appealed to General Henry H. Arnold, Chief of Staff of the Army Air

Force, who was convinced by the idea of using the Philippines as a base for the B-29. This plane, the heaviest yet build, the longest-ranged, the most capable of bombers, could reach

Japan from the islands, and the secure sea routes of supply to those bases were far more promising than the tedious route by which the only other available base, China, could be

reached.

King’s plan aimed, among other things, at taking

the Marianas islands in the central Pacific, lying like a barrier across the direct route from Hawaii to the Philippines. Although the Pacific Fleet’s planners were lukewarm at best to the

idea (and had, in private conference with MacArthur’s command, preferred the southern approach), King’s idea appealed to General Henry H. Arnold, Chief of Staff of the Army Air

Force, who was convinced by the idea of using the Philippines as a base for the B-29. This plane, the heaviest yet build, the longest-ranged, the most capable of bombers, could reach

Japan from the islands, and the secure sea routes of supply to those bases were far more promising than the tedious route by which the only other available base, China, could be

reached.

It could not have come as a great surprise then that at Cairo in November 1943, the Combined Chiefs of Staff, the supreme Allied military decision-making organ, admitted the Marianas to the circle of targets for 1944, tentatively setting October 1st as the date.

Two powerful allies were sitting in Washington as the Pacific Fleet was beginning to execute its part in what were the current war plans. Designated as a flank protection to MacArthur, in November 1943, American Marines landed on Tarawa in the Gilbert Islands, as part of Operation GALVANIC. GALVANIC opened up airfields to U.S. Army Air Force use as a preliminary to the next, more important operation.

This next operation, FLINTLOCK, aimed at places in the Marshalls. But with the CCS’ new directive, Admiral Nimitz had a new plan made, which incorporated a much more active role in the Central Pacific. New on the target list were the Palaus and the Marianas. A change in the FLINTLOCK operation took note of this new, westward reaching campaign plan. It designated Majuro, a superb anchorage, which had not been mentioned in the original plans. When the U.S. forces descended on the Marshalls, in February 1944, they won comparatively easy victories.

At the same time, Nimitz was reworking his plans in Pearl Harbor, speeding up the schedule. He proposed two different schemes for his next operations. The route to be pursued was clear: Truk, in the Carolines, then the Marianas, then the Palaus were to be targeted. The alternative was to bypass Truk; that plan would allow a Marianas landing on June 15th, 1944.

The Pacific Fleet staff was not enthusiastic. It did not really believe in the Marianas as a target - no harbors, and a prospective heavy cost of live, were the main concerns. But King would not have it. Correctly judging the advantages of owning the Marianas, he did not even try to argue. In firm terms he told Nimitz that it was the JCS decision to take the Marianas; Nimitz was not to concern himself with that question.

In mid-February, air attacks on Truk showed that respected fortress to be little more than an abandoned fleet anchorage. Without the Japanese fleet operating from there, and with no air force to speak of, Truk seemed well worthy of bypassing. All this in mind, Nimitz received a directive from the Joint Chiefs on March 12th, 1944, ordering him to take the Marianas on June 15. The operations would be given the name FORAGER.

As the U.S. went through the long process of deciding on a correct strategy, the same problem plagued the Japanese.

Japanese Replies

The six-month campaign for Guadalcanal had considerably drained Japanese resources. The Combined Fleet at Truk was nevertheless fairly certain that the Americans could yet be stopped in the Solomons, and Admiral Yamamoto played on this. In launching Operation I (I-Go) in early spring, he moved carrier squadrons to bases around Rabaul and commenced air offensives towards Guadalcanal. But his ploy failed terribly. Badly mauled, the Japanese squadrons succeeded in sinking only a destroyer and various small and merchant ships. Admiral Yamamoto himself would not survive his operation: in April, going by way of plane to Bougainville in the northern Solomons to encourage his fliers, he was jumped by long-range fighters and shot down.

His replacement was Admiral Koga Mineichi,

an erstwhile Vice Chief of Naval Operations and the China Area Fleet. Koga’s command was set up at Truk, aboard battleship Musashi. His staff prepared what would remain the

Combined Fleet’s strategic conception for the coming year, the ”Z” plan. According to this plan, the Combined Fleet would be used to defend an outer perimeter containing the

Solomons, Gilberts and Marianas up to the Aleutians. Koga’s fleet, in an eerie reminder of the single-mindedness of Japanese high command, clung to the concept of the

”Decisive Battle”, but eventually had to considerably decrease the size of territory it could defend. After the disastrous American raids on Rabaul in late autumn (compounding the

decimation of Japanese cruiser strength with the destruction of the newly-reformed carrier air units), it became quickly evident that the Solomons could no longer be considered

to be part of the perimeter, and by extension, the Marshalls and Gilberts, which served little purpose anyway, were not to be the place of the ”Decisive Battle” anymore. Strapped

of these obligations, the Combined Fleet nevertheless remained at Truk until February 1944, when, just before the U.S. raid, it moved to Palau on February 10th. There it remained

for one and a half months. On the final days of March, the U.S. raided Palau from where the Japanese fleet had escaped not a week before. The fleet lost a few minor units and

one major person: Admiral Koga, who was lost when his plane crashed into the sea in a storm.

His replacement was Admiral Koga Mineichi,

an erstwhile Vice Chief of Naval Operations and the China Area Fleet. Koga’s command was set up at Truk, aboard battleship Musashi. His staff prepared what would remain the

Combined Fleet’s strategic conception for the coming year, the ”Z” plan. According to this plan, the Combined Fleet would be used to defend an outer perimeter containing the

Solomons, Gilberts and Marianas up to the Aleutians. Koga’s fleet, in an eerie reminder of the single-mindedness of Japanese high command, clung to the concept of the

”Decisive Battle”, but eventually had to considerably decrease the size of territory it could defend. After the disastrous American raids on Rabaul in late autumn (compounding the

decimation of Japanese cruiser strength with the destruction of the newly-reformed carrier air units), it became quickly evident that the Solomons could no longer be considered

to be part of the perimeter, and by extension, the Marshalls and Gilberts, which served little purpose anyway, were not to be the place of the ”Decisive Battle” anymore. Strapped

of these obligations, the Combined Fleet nevertheless remained at Truk until February 1944, when, just before the U.S. raid, it moved to Palau on February 10th. There it remained

for one and a half months. On the final days of March, the U.S. raided Palau from where the Japanese fleet had escaped not a week before. The fleet lost a few minor units and

one major person: Admiral Koga, who was lost when his plane crashed into the sea in a storm.

Lost with him was his chief-of-staff, Vice-Admiral Fukudome Shigeru, who, however, did not die: he crashed in the sea near the island of Cebu and was rescued by local fishermen, and turned over to local guerrillas. With him he carried a briefcase containing, among other things, a copy of the operations plan known as ”Z”. Fukudome later escaped captivity, and reported the fact of the loss.

Koga’s successor, Admiral Toyoda Soemu, led the Combined Fleet from Tokyo. It was, no longer, a fleet combined: by late April, powerful elements had fled to Singapore, including battleships Yamato and Nagato, and the heavy carriers Shokaku, Zuikaku and Taiho. Other units, including battleship Musashi and carriers Hiyo and Junyo, were in Japan’s Inland Sea. Toyoda’s fleet’s main unit was the Third, or Mobile, Fleet, headquarters on the brand-new carrier Taiho. The new designation ”Mobile” had an important connotation. Instead of remaining separated into a battleship, a cruiser, and a carrier fleet (to roughly give the meanings of 1st, 2nd and 3rd Fleets), the Japanese now operated in a task force format similar to the American concept. And Commander Third Fleet, the carrier force commander, would control this force.

Since late 1942, the man in charge of this force had been Vice-Admiral Ozawa Jisaburo, a fearless, aggressive, talented officer, who was just the right man to lead the IJN’s still most potent weapons. In the peace and quiet that was Singapore, Ozawa’s aircrews received some badly needed training, but not enough. On May 11th, only a month and a half having been spent at Singapore, the Mobile Fleet left for the anchorage of Tawi-Tawi. In Ozawa’s pockets by this time (and since May 3rd) were two distinct operational plans: KON, a limited effort to repulse enemy attacks along a perimeter stretching from Japan proper through the Marianas and Palaus to New Guinea, thence to the Dutch East Indies. The Combined Fleet was to conduct reinforcement and attack operations within this perimeter. The second plan was for A-Go, ”A” Operation, and once more was a call for the ”Decisive Battle”. Two scenarios were worked out, one for an invasion of the Palaus and another for the Marianas. In each case, the Mobile Fleet was to sortie in force to destroy an enemy fleet weakened by relentless air and submarine attack. At Tawi-Tawi, the Singapore elements of the Mobile Fleet were joined, on May 15th, by the rest of the fleet, including the 2nd and 3rd carrier divisions and battleship Musashi.

Once within the anchorage, however, it soon became apparent that although someone would be decimated and blooded before any battle could be fought, and it would not be the Americans. Tawi-Tawi, for all its values, was not a healthy place for a force such as Ozawa’s. The anchorage was little more than that: a place where shelter from the elements could be found. Without air facilities, the carriers had to sortie to afford their crews flight training. Without adequate geographical shielding, the anchorage offered U.S. submarines an excellent ambush point. The first victim of both facts was destroyer Yukikaze, damaged by a torpedo while escorting a flattop out to sea. As the battle of the Philippine Sea approached, the Japanese casualties mounted.

Setting the Stage:

May 27th to June 14th

On May 27th, the 41st U.S. Infantry division was landed by elements of Vice-Admiral Thomas C. Kinkaid’s 7th Fleet on Biak, a large island off the coast of New Guinea. By this time, FORAGER’s invasion forces, though not the carriers, were already at sea, heading for the Marianas. The two-prong attack strategy was working out.

The Japanese reacted quite more ambitiously than could be expected. Regarding Biak as a possible place to hit the Americans hard, immediately after the invasion, strong air units were deployed there. But Admiral Ozawa countermanded the concept of employing the entire Mobile Fleet. Since a limited reply would fall under the plans designated in KON, so the operation was named when it commenced on May 30th, with the sortie of the 5th Heavy Cruiser division, destroyers, and battleship Fuso to Davao on Mindanao. Going out of Tawi-Tawi, the Fuso group was sighted by a submarine. Departing Davao again on June 3rd, the KON force received a message from Tokyo suspending the operation temporarily at midnight. They returned to Davao the next day.

Whilst the force at Davao was waiting, the submarine Harder caught and sank the destroyer Hayanami and the destroyer Minatsuki off Tawi-Tawi.

On June 6th, with the prodding of the local Area Army, Combined Fleet renewed the orders for the commencement. At the same time, TF-58 departed Majuro in force, under Vice-Admiral Mitscher, with a different target.

Two days later, the second attempt of the KON Force to reach Biak ended in failure when the destroyers carrying troops were bounced by a cruiser force commanded by

Vice-Admiral Victor A.C. Crutchley, RAN, and elected to retire without offering battle. The next night, the Mobile Fleet was informed that Majuro was devoid of carriers. Throughout

the fleet, tension rose as the expected Decisive Battle drew nearer. Not long thereafter, the submarine Harder blew apart another Japanese destroyer, Tanikaze, off

Tawi-Tawi.

Two days later, the second attempt of the KON Force to reach Biak ended in failure when the destroyers carrying troops were bounced by a cruiser force commanded by

Vice-Admiral Victor A.C. Crutchley, RAN, and elected to retire without offering battle. The next night, the Mobile Fleet was informed that Majuro was devoid of carriers. Throughout

the fleet, tension rose as the expected Decisive Battle drew nearer. Not long thereafter, the submarine Harder blew apart another Japanese destroyer, Tanikaze, off

Tawi-Tawi.

June 10th offered another surprise: Operation KON would not be abandoned, but strengthened with the most powerful single units the IJN had to offer, the battleships of Vice-Admiral Ugaki Matome's 1st Battleship Divison, Yamato and Musashi. Ugaki would take command over this renewed relief effort and took his ships out of Tawi-Tawi at 1800, heading for Halmahera in the Celebes to rendezvous with the rest of his force.

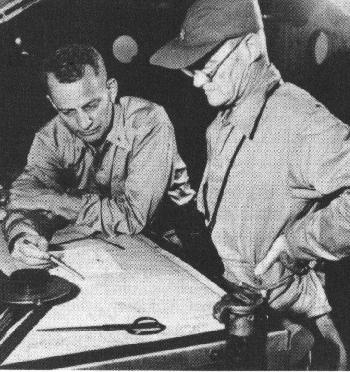

Ugaki had begun marshalling his forces in Tawi-Tawi, Mitscher’s Task Force 58 refueled just out of range from enemy planes in the Marianas and closed the islands.

The next day, Mitscher consulted his staff for the air operations to begin the next day. His staff advised that it would be possible to launch a fighter-sweep that afternoon, probably

taking the Japanese by complete surprise even though planes had already spotted TF58. Mitscher concurred quickly. At 1300, the first of 213 fighters and ten supporting bombers

with life rafts rushed off the deck. After forming into squadrons, the planes set off, reaching their targets on Rota, Saipan, Tinian and Guam a little over an hour after launch. They

bombed and strafed airfields and shot down intercepting planes. Returning planes came over the Task Force at 1630 and continued to come for some time. The strike had been an

unqualified success. Eleven fighters had been lost, but U.S. claims ran to 150 planes destroyed (of which the Japanese admitted thirty-six). Even though the true numbers are hard to

establish, it is virtually certain that this initial strike hit the Japanese hard; and it established an ominous precedent in the reports that Vice-Admiral Kakuta Kakuji, Commander of the

First Air Fleet, sent out. Claiming major American losses and slight Japanese damage, he heightened Japanese spirits with information that had no basis in fact.

Ugaki had begun marshalling his forces in Tawi-Tawi, Mitscher’s Task Force 58 refueled just out of range from enemy planes in the Marianas and closed the islands.

The next day, Mitscher consulted his staff for the air operations to begin the next day. His staff advised that it would be possible to launch a fighter-sweep that afternoon, probably

taking the Japanese by complete surprise even though planes had already spotted TF58. Mitscher concurred quickly. At 1300, the first of 213 fighters and ten supporting bombers

with life rafts rushed off the deck. After forming into squadrons, the planes set off, reaching their targets on Rota, Saipan, Tinian and Guam a little over an hour after launch. They

bombed and strafed airfields and shot down intercepting planes. Returning planes came over the Task Force at 1630 and continued to come for some time. The strike had been an

unqualified success. Eleven fighters had been lost, but U.S. claims ran to 150 planes destroyed (of which the Japanese admitted thirty-six). Even though the true numbers are hard to

establish, it is virtually certain that this initial strike hit the Japanese hard; and it established an ominous precedent in the reports that Vice-Admiral Kakuta Kakuji, Commander of the

First Air Fleet, sent out. Claiming major American losses and slight Japanese damage, he heightened Japanese spirits with information that had no basis in fact.

The attack must have startled the Combined Fleet, which was unprepared for this contingency. Orders that had gone to the air units in the Central Pacific to converge on Biak

were cancelled and now pointed those air units at the Marianas. But as of yet, nothing indicated an invasion. The KON operation proceeded as planned. On June 12th,

Ugaki’s battleships dropped anchor at Halmahera. There they remained the next day, which the U.S. forces used to good effect in the Marianas. Planes intercepted a

convoy heading for Japan, and continued their bombardments of the island’s airfields and fixed defenses as the carriers rounded the southern tip of the Marianas and entered

the Philippine Sea.

The attack must have startled the Combined Fleet, which was unprepared for this contingency. Orders that had gone to the air units in the Central Pacific to converge on Biak

were cancelled and now pointed those air units at the Marianas. But as of yet, nothing indicated an invasion. The KON operation proceeded as planned. On June 12th,

Ugaki’s battleships dropped anchor at Halmahera. There they remained the next day, which the U.S. forces used to good effect in the Marianas. Planes intercepted a

convoy heading for Japan, and continued their bombardments of the island’s airfields and fixed defenses as the carriers rounded the southern tip of the Marianas and entered

the Philippine Sea.

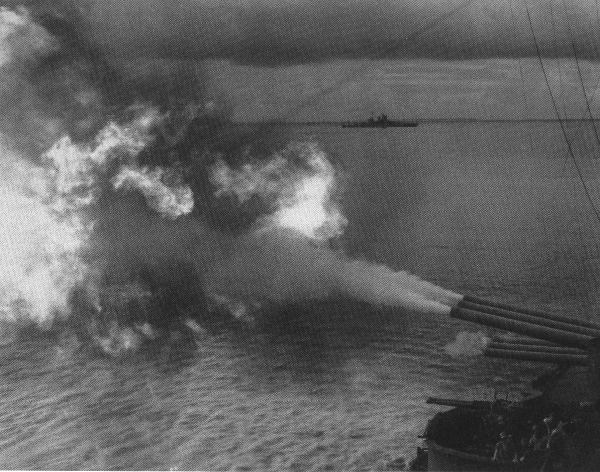

The true reason of this powerful air raid became apparent when on June 13th, Vice-Admiral Willis A. Lee’s fast battleships exercised a bombardment of coastal defenses on Saipan. Without proper training, the shelling was unproductive - ”ploughing the fields, harvesting the crops, while simultaneously adding iron to the soil”, as one battleship sailor mocked. The same morning, at 1100, Ozawa’s forces sailed from Tawi-Tawi to Guimaras in the Philippines. This was no reaction to the Marianas operations, but a longer-planned move, which did not go unnoticed either. The submarine Redfin sighted Ozawa and gave off a contact report. Shortly past 1930, Ozawa dispatched the message ”Prepare for A-Go” and cancelled the KON operation, ordering Ugaki to rejoin the fleet, with a rendezvous set in the Philippine Sea. The battleship bombardment must have instilled fears of a invasion of Saipan (as it had once before at Ponape).

Guimaras was reached by Ozawa at 1600 on the 14th, commencing refuelling to be ready to leave early the next day. Meanwhile, the American support forces had arrived in force off Saipan and commenced with pre-invasion shelling as well as minesweeping. The fast carriers had other goals in mind.

Vice-Admiral Raymond Spruance, in command of 5th Fleet, commanding the operations overall, received information of impending Japanese air reinforcements to be flown in via Iwo and Chichi Jima in the Bonin Islands. Since any fleet engagement with the Japanese was still a long time off, Spruance elected to despatch two of his carrier groups to hit the islands and prevent the aircraft from reaching the battle area. Under Rear-Admiral J.J. ”Jocko” Clark, TG 58.1 departed north, under Rear-Admiral William Keen Harrill TG 58.4 joined. The command situation was peculiar, for neither commander had overall command. Mitscher trusted his commanders would find their way around, but throughout the separate voyage, the two detached admirals would lock horns over the way their mission should be conducted.

The initial working-over given to the Japanese planes in the Marianas had substantially weakened a leg of the tripod that the Japanese had set up for their decisive battle. A second, the submarine force, was almost an endangered species. The Japanese had deployed their submarine force expecting an assault on Palau, which obviously was mistaken. But more serious than this miscalculation was the way in which the submarines were employed. Moved into a rigid scouting line whose position was broadcast via radio, it offered American radio intelligence the excellent chance to win a crippling victory. Most famous was U.S.S. England’s six sinkings record, but overall, seventeen of 25 operating submarines were destroyed.

The Final Days: June 15th to June 18th

In the early morning hours of June 15th, 1944, from the decks of the transports off Saipan soldiers climbed into their landing craft, bobbing in the seas below, and headed for the beaches. Landing there at 0845, they were awaited by deadly fire and powerful defences, which they nevertheless, aided by gunfire and air support, and with a firm will, overcame during the day. By nightfall, there was a firm U.S. foothold on Saipan.

An hour after the landing, Tokyo at 0955 despatched

the order to the Mobile Fleet ”Initiate A-Go”. Five minutes later, a well-prepared Ozawa began his sortie from Guimaras. Under the watchful eyes of Filipino coast watchers, his powerful

nine-carrier force moved north, heading for San Bernadino Strait. There, at 1822, the submarine Flying Fish caught sight of the Japanese fleet. An hour later, the submarine

Seahorse had sighted Ugaki’s KON units.

An hour after the landing, Tokyo at 0955 despatched

the order to the Mobile Fleet ”Initiate A-Go”. Five minutes later, a well-prepared Ozawa began his sortie from Guimaras. Under the watchful eyes of Filipino coast watchers, his powerful

nine-carrier force moved north, heading for San Bernadino Strait. There, at 1822, the submarine Flying Fish caught sight of the Japanese fleet. An hour later, the submarine

Seahorse had sighted Ugaki’s KON units.

Aboard Lexington, TF-58’s flagship, the certainty of Ozawa’s coming (which had already been indicated in CinCPac Intelligence Summaries a few days earlier) had been concluded from the received reports and the presumed intentions of the Japanese. Now, the question was what to do. At first, the decision was simple: nothing at all, just yet. The fast carriers had spend the better part of the last four days hitting Japanese installations in the Marianas and had largely negated Japanese air power there. Besides late-night nuisance raids, hardly a reaction had come from the Japanese.

On June 16th, Clark’s and Harrill’s forces finally reached their targets, hitting Chichi, Haha and Iwo Jima in the Bonins, and destroying the majority of Japanese air units there. The carriers remained in the vicinity of the islands, hoping to get in another strike the next day. In the meantime, Ugaki’s forces refuelled (at 1100) off the Philippines from the 1st Supply Force and met up with the rest of Ozawa’s forces at 1750. The Mobile Fleet then commenced refuelling. The oil was Tarakan fuel oil, utilized without refinement. Although perfectly useable, it was a dangerous fuel, and would prove hazardous. Ozawa remained tracked: his 2nd Supply Force, which had taken a more northerly course than the main force, was spotted by the submarine Cavalla, which reported the force and then planned to go off again to its patrol zone. But ComSubPac Vice-Admiral Lockwood had other plans. He ordered Cavalla to follow the track of the enemy force, hoping that, as with the pot of gold at the end of the rainbow, this guide would lead to a more valuable target.

As June 17th dawned, the U.S. carriers prepared to engage in battle. They let go of their targets ashore, conducted a final refuelling, and established TG 58.7, the fast battleship force, under Willis Lee. From the north came Keen Harrill’s force, followed in the evening by Clark’s carriers that had got in another strike at the enemy on Iwo and Chichi Jima. Just then, urgent messages called for the forces to expedite their returns. The Japanese were closing.

In fact, the Japanese were not only closing, but also found. Cavalla, trailing her tanker quarry, had unsuspectingly bounced the entire Mobile Fleet at 2100 hours on June 17th, north of Palau. The submarine did not attack but reported the enemy force and began to trail it. That night, Ozawa ended his final preparations, bringing his fleet into battle dispositions. For his first sortie into battle, Ozawa deployed into three forces: ”A” Forces, which he lead himself, composed of the three heavy carriers, plus escorts. ”B” Force, composed of the medium Hiyo and Junyo and a light carrier, plus escorts. And ”C” Force, lead by Vice-Admiral Kurita Takeo, composed of the majority of heavy ships and three light carriers. ”C” Force would be deployed ahead of the Japanese forces to the east, its heavy anti-air batteries supposed to be powerful defences even before the American planes could reach the heavy carriers. Thus Ozawa steamed east into his first carrier battle.

The Battle of the Philippine Sea: June 18th to June 20th, 1944

The morning of Sunday, June 18th, dawned a clear day over the Philippine Sea, but through the day, it would become slightly more cloudy. Ideal conditions for a successful attack, if the Japanese chose to use them. With clouds to hide in and a relatively clear sight nonetheless through the gaps in between, the weather offered a little bit of both. Air operations didn’t wait until the sun had dawned, nonetheless. At 0532, the first American carrier scouts departed their home bases, forming into scouting teams of a fighter and a bomber, and headed out to the west covering narrow 10° sectors. At 0600, their Japanese counterparts followed suit, sending out a combination of carrier attack planes and floatplanes. Two hours later, the first battles ensued as scouts met each other. A B5N ”Kate” was flamed by an Essex scout team of a SB2C Helldiver and a F6F Hellcat. Two E13A ”Jake” reconnaissance planes failed to return as well.

At midday, Ozawa had all his remaining scouts back aboard, and commenced a new round of reconnaissance flights. Again a mixture of float- and carrier planes took aloft, searching for the enemy that Ozawa had now closed measurably.

This time, his pilots had more luck. At 1514, a Japanese scout snooped upon what probably was Harrill’s Task Group, reporting this find back to the Mobile Fleet. Ozawa received the information at 1530. More contacts were reported at 1600, but Ozawa rightly determined not to launch. His inexperienced airmen could hardly have managed the dusk strike and night landing that a launch so late in the day would have caused.

However, this was not quite the perception that Rear-Admiral Obayashi Sueo had. His Carrier Division 3, light carriers Chitose, Chiyoda and Zuiho, began launching a strike of A6M Zeke fighter-bombers and B6N Jill torpedo planes at 1637. Not much thereafter, however, Admiral Ozawa’s Operations Order 16 for the coming day arrived on the flagship of the division, Chitose. Ozawa’s orders postulated that the Mobile Fleet would retire through the night and hit the enemy first thing next morning. Thus countermanding Obayashi’s orders, the CarDiv3 strike was recalled to the decks, losing a Zeke.

At 2100, Ozawa ordered Vice-Admiral Kurita Takeo out east with CarDiv3, the First Battleship Division, and various other powerful vessels. There, a hundred miles in front of Ozawa, Kurita was to form a barrier between the main fleet and the Americans.

June 19th

Through the night, snoopers from both sides sighted their respective targets. Flying boats and land-based planes operating from such places as Manus in the Admiralties and from tenders off Saipan were the U.S. scouts, while similarly, flying from Palau, Truk, and other bases were the Japanese scouts. The U.S. sighting came from a PB4Y ”Liberator” out of Manus, operating under the command of Douglas MacArthur’s South West Pacific forces. The heavy bomber stumbled upon the main Japanese force under Ozawa and despatched a contact report. That report never reached Spruance. Though caught by vessels further out, at Eniwetok, these ships did not bother to relay the information. Without knowing anything about the whereabouts of the Japanese carriers, except for knowing that their position was nearby, Spruance chose to remain where he was, covering the landing areas. For the past days he had worried about being surprised by the Japanese in an end-run around his fleet and towards the landing beaches. Naturally, without knowing the position of the enemy, Spruance was not inclined to head out blindly. So starting at 0218, Spruance’ carriers launched scouts out to the east to determine the enemy’s position.

Meantime, the Japanese were continuing their operations in the planned way. Kurita reached his covering position at 0415, completing the Japanese move into battle dispositions. Ozawa’s job of scouting was easier - he knew the approximate whereabouts of the American forces, still convinced of being able to read Spruance’ mind. At 0430, the Mobile Fleet commenced the launch of E13A ”Jake” search planes from the battleships and cruisers of ”C” Force, followed 45 minutes later by a second-phase search.

Sunrise that day was at 0542, a fair day which would yet bring squalls and clouds, and a quarter hour later, the first American planes arrived over Orote Field, Guam, to neutralize

the field and destroy planes commencing their own launch from there. Only about fifty planes were still stationed on the air base, but Admiral Kakuta was determined to make most of

what he had. Planes from his force were already engaging the American ships in small skirmishes, commonly ending in the attacker’s destruction.

Sunrise that day was at 0542, a fair day which would yet bring squalls and clouds, and a quarter hour later, the first American planes arrived over Orote Field, Guam, to neutralize

the field and destroy planes commencing their own launch from there. Only about fifty planes were still stationed on the air base, but Admiral Kakuta was determined to make most of

what he had. Planes from his force were already engaging the American ships in small skirmishes, commonly ending in the attacker’s destruction.

Secure in his knowledge of the enemy’s presence, however, Spruance soon chose at least to maneuver out to the west, turning west by southwest at 0619. But conditions were not favorable to a swift American advance to the west. An westerly wind necessitated turning back east for all launches of planes, and for four hours until 1023, barely any progress was made.

Ozawa definitely had the initiative now and used it. When at 0730, a Jake sighted the task groups of Harrill and Lee, operating as the two horizontal bars of the ”F” formation of U.S. task groups, Ozawa had all the information that he needed. His force was ideally placed, and so Ozawa prepared for the launch. Again, however, Rear-Admiral Obayashi, commanding the carriers in Kurita’s force, proved too impatient for his superior officer. At 0800, two path finding B5N ”Kate” torpedo-planes lifted off the decks of the small carriers, followed twenty-five minutes later by the strike force of 69 planes. Obayashi’s reluctance to wait for orders cost the Japanese any coherency in the attack effort. The 653rd Air Group would attack far ahead of the other Japanese forces.

Ozawa had been awaiting further information on his enemy, but when none came, at 0857, Ozawa commenced the launch of his own 601st Air Group. The Second Carrier division under Rear-Admiral Joshima held back for the time being. Ozawa had probably made his first error of the battle: by letting Obayashi’s insubordination stand, and by not committing himself fully to a first-strike victory, Ozawa had forgone the only chance to overwhelm the powerful U.S. defenses. He would soon have reason to regret it.

But other problems were creeping around his force. As the Zekes, Judys, and Jills thundered aloft from the decks of the Japanese carriers, nearby the flagship Taiho, a periscope broke the surface of the calm Philippine Sea, scanning around. At its control was Commander James Blanchard, commanding submarine Albacore. Vice-Admiral Lockwood had ordered his boat and three others to roam the seas around where Cavalla had sighted the Mobile Fleet’s oiler force. Blanchard had done so: and fixed in his sights now were three carriers. Blanchard selected the second one and closed calmly. However, when 5300 yards distant, another look through the periscope revealed that the Torpedo Data Computer, controlling the torpedo setup, had malfunctioned. Blanchard fired six torpedoes aiming with the thumb and went deep as a trio of Japanese destroyer came charging for him.

Taiho made no evasive maneuvers as the torpedoes plowed towards her. However, Blanchard’s misfortune with the TDC translated in just one hit. Shortly after 0910, a single torpedo hit the ship starboard near the forward gasoline tanks, rupturing some gas and oil lines and jamming the elevator. But the vessel’s speed was not impeded and Taiho seemed quite unharmed: she slowed just slightly, no fires erupted, and her damage control officer could not recognize any great danger to the ship.

Meanwhile the Japanese attack groups flew on, passing over ”C” Force on the way and getting mauled by their own flak, losing two planes and having eight damaged. At about the same time, alarms sounded on the carriers of Task Force 58: radars had detected the incoming strike planes from ”C” Force.

At 1005, Admiral Mitscher ordered all fighters readied and prepared for launch, and all bombers off the decks. Sent east, the bombers were to hover and wait. At 1019, the execute order came, a four minutes later, the first reinforcements for the Combat Air Patrol took off from the decks of the fast carriers, with the bombers slowly heading east to circle outside the combat zones. 450 Hellcats were now free to operate from the flight-decks of the carriers.

At the same time, Admiral Joshima’s CarDiv2 finally commenced the launch of its planes, adding 47 planes to the attack waves.

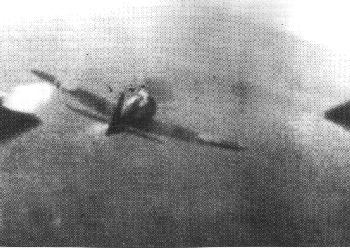

Admiral Mitscher had launched 150 additional Hellcats for his air patrol by 1040. Fifteen minutes earlier, the first Hellcats had engaged the Japanese attackers. The ensuing

action was badly one-sided. As the Hellcats tore into the Japanese formation, the Japanese airmen evaded and twisted, but to little avail. This first raid, from Obayashi’s carriers,

had many of its Zekes loaded with bombs, which made their flight characteristics sluggish. The furball rolled towards the initial line of U.S. vessels, the battleships of Task Group

58.7. Here, what remained of the Japanese planes broke into dives, desperately seeking targets for their bombs. A single bomb tore into South Dakota, damaging the battleship.

But the cost of this Japanese success was horrendous. Only 27 of the 71 planes launched returned to their carriers, many of those damaged.

Admiral Mitscher had launched 150 additional Hellcats for his air patrol by 1040. Fifteen minutes earlier, the first Hellcats had engaged the Japanese attackers. The ensuing

action was badly one-sided. As the Hellcats tore into the Japanese formation, the Japanese airmen evaded and twisted, but to little avail. This first raid, from Obayashi’s carriers,

had many of its Zekes loaded with bombs, which made their flight characteristics sluggish. The furball rolled towards the initial line of U.S. vessels, the battleships of Task Group

58.7. Here, what remained of the Japanese planes broke into dives, desperately seeking targets for their bombs. A single bomb tore into South Dakota, damaging the battleship.

But the cost of this Japanese success was horrendous. Only 27 of the 71 planes launched returned to their carriers, many of those damaged.

At 1057, the fighter control officer noted his radar screens were clear of targets, and in the short lull which began, Task Force 58 hurriedly rearmed and refueled its fighters. The lull was short indeed: at 1107, the first new bogeys appeared on the screens, this one the raid launched by Ozawa’s 601st Air Group, the most powerful single blow to land on the U.S. fleet in this engagement. At 1139, Essex planes intercepted the raid, six minutes later followed by other Navy fighters from most other carriers. Again, the dogfights whirled over the Task Force, as slowly, the embattled Japanese drew closer to the American forces. At 1150, the battleships again were attacked, and ten minutes later, the first Japanese attacks on the fast carriers were delivered when the remnants of the Japanese strike hit Admiral Reeves Task Group 58.3 and Admiral Montgomery’s Task Group 58.2. Neither force sustained anything but superficial damage, and at 1215, the radar screens once more showed no enemy planes aloft. Only 31 planes of Ozawa’s large 129-plane strike returned to their carriers. These, in the meantime, had launched their final strike of day, Raid IV, starting at around 1100.

The gods of war, who had smiled upon the Japanese Navy on so many occasions, were now playing a cruel game with the Japanese. As aircrew after aircrew and plane after plane met its demise at the hands of anti-air artillery and fighter planes, the Mobile Fleet’s precious carriers once more were targets for an attack.

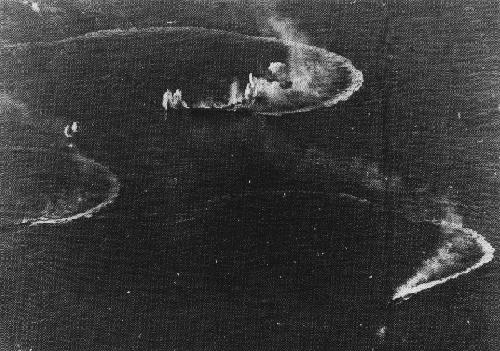

This time it was Shokaku, veteran of Pearl Harbor and three carrier battles. The big flattop was flying off and landing planes, the planes that comprised Raid IV and various Zekes of the Combat Air Patrol. The whole screen seemed totally oblivious to the threat from submarines. This was luck for Cavalla, commanded by Hermann Kossler, whose periscope had pierced the surface of the Philippine Sea at 1152. Kossler quickly closed the carrier, reaching 1200 yards without being sighted or otherwise detected. He fired six torpedoes, going deep as finally a Japanese destroyer engaged him. Three torpedoes slammed into the carrier at 1220, which immediately erupted into flames. Here, as in Taiho, the gasoline tanks were ruptured and the deadly fumes spread through the ship. The resulting fires were difficult to control, even for the experienced crew of Shokaku, and quite soon the damage control teams lost their battle. At 1500, a powerful explosion doomed the carrier.

While Shokaku was struggling for her survival, the air strike, which Joshima had dispatched in the course of the morning, reached the American force. Harrill’s carrier force was their target, but this time, the Japanese were not in for the usual rough treatment. Although they again scored no hits, they suffered only seven losses.

Raid IV did not encounter any vessels were it was looking, so the main element of the 82 planes shaped course for Guam. Its course led it right into the intercept vectors of the fighters of Admiral Montgomery’s TG 58.2. It was a massacre. The Japanese planes were bounced by waves of Hellcats, and flak from the ships subtracted still more planes. The Japanese slowly made their way to Guam, were more surprises awaited them: American fighters were all around the planes now attempting to land. By half past three, Raid IV had been decimated. By a cruel coincidence, the Japanese would have still worse worries a few minutes later.

Shortly after 1530, a violent explosion erupted in Taiho's hangar deck. Her armored flight deck buckled, then broke up, her bottom was holed and fires spread out of control. Ozawa’s flagship was doomed, by the distribution of the volatile oil and aviation fuel gases through out the ship. Ozawa left his ship not much after the explosion, prodded to do so by his staff. At 1828, Taiho went under in another great detonation, heeling over on her side and beginning her voyage to the bottom.

This time also terminated air operations. Final sweeps over Orote by U.S. planes had bagged the occasional plane, but more important targets awaited the Americans. The next day might yet offer the American airmen the chance to sink themselves a carrier.

June 20th

During the afternoon of June 19th, Vice-Admiral Spruance had appraised Vice-Admiral Mitscher that he intended to strike the Japanese fleet on the morning of June 20th, if the enemy’s position was known with sufficient accuracy. As of the evening of June 19th, however, such accuracy was lacking. For all it was worth, especially in Spruance’s mind, Ozawa could be anywhere, to his north, south, or west, at distances ranging from 200 to 350nm. His only information was the knowledge of the positions of the torpedoed carriers (though only Shokaku was presumed destroyed), which was old information by nightfall. Spruance first set to work on more mundane matters, recalling Vice-Admiral R.K. Turner’s amphibious shipping to the Saipan beaches from their out-of-the-way position 200nm to the east. Then, he dispatched Rear-Admiral Harrill’s Task Group, since the cautious Commander, TG58.4 had reported that he was low on fuel for his destroyers. It was 2000 on June 19th when finally, after having recovered their airgroups, the remaining fast carriers took of in pursuit of Ozawa’s crippled fleet.

Ozawa had initiated his retreat at the same time, positively shocked at the extend of his losses, and quite unable to resume his aerial offensives the next day, as originally planned. No word had come from Kakuta’s land-based air units. However, from Tokyo word had come that the Combined Fleet desired the attacks to be renewed, if possible, on the 22nd. Obviously, Tokyo was quite aware of the serious trouble that the loss of the Marianas would be to Japan.

However, Ozawa’s primary concern was now fuel. He scheduled a refueling for the next day, aware that he would need it.

At half past five in the morning, both sides commenced the day’s air operations with searches, none of which found anything of note. At 1330, another search group took off

from the American flattops, aboard which anxiety was spreading that the Japanese had gotten away. Finally, this search yielded a sighting of the Mobile Fleet: at 1540, an Enterprise

scout found the Japanese. Twenty minutes later, Mitscher was sitting down with his staff and airmen to see what could be made of this. The news were not great: a strike could be

flown - just one before darkness would completely prevent strike operations --, but it would be a great gamble because the range was long and the returning planes would have to land

in darkness. At 1610, the pilots were already scrambling out of the ready rooms. Many of them had uttered respectful whistles when shown the distance of the enemy force, quickly

realizing what it meant. But the chance to hit a carrier was not to be missed by anyone, and when at 1621, the carriers swung into the wind, 215 carrier planes were bound to launch to strike

the enemy fleet not seen by carrier pilots since October 1942.

At half past five in the morning, both sides commenced the day’s air operations with searches, none of which found anything of note. At 1330, another search group took off

from the American flattops, aboard which anxiety was spreading that the Japanese had gotten away. Finally, this search yielded a sighting of the Mobile Fleet: at 1540, an Enterprise

scout found the Japanese. Twenty minutes later, Mitscher was sitting down with his staff and airmen to see what could be made of this. The news were not great: a strike could be

flown - just one before darkness would completely prevent strike operations --, but it would be a great gamble because the range was long and the returning planes would have to land

in darkness. At 1610, the pilots were already scrambling out of the ready rooms. Many of them had uttered respectful whistles when shown the distance of the enemy force, quickly

realizing what it meant. But the chance to hit a carrier was not to be missed by anyone, and when at 1621, the carriers swung into the wind, 215 carrier planes were bound to launch to strike

the enemy fleet not seen by carrier pilots since October 1942.

It was two hours and 300 miles later that the air strike reached the Japanese fleet. There were 20 minutes of daylight left, so time was of the essence as the American air groups formed up. The Japanese were poorly defended: few fighters were aloft and the carrier groups were separated. Immediately in front of the American forces was the oiler group of six tankers and six destroyers; to the west was ”C” Force; to the west-north-west was ”B” Force; and north by north-west was the decimated ”A” Force. A single American air group hit on the oilers; three went for ”C” Force, six for ”B” Force and three more for ”A” Force. They would only have this shot at the quickly retiring enemy.

The main hamper to a successful strike were the bomb-laden Avengers, not so much for their presence but for their useless load. The old adage was that ”if you want to fill a ship with smoke, use bombs; if you want to fill it with water, use torpedoes”. But torpedoes had been useless for the better part of a year of fast carrier operations, and bombs were by now the weapon of choice for the Avengers. But bombs didn’t sink capital ships unless they were vulnerable, and without fueled planes aboard the Japanese carriers weren’t especially vulnerable. Consequently, Ryuho and Zuikaku, hit by bombs, did not suffer great damage. More severe damage was suffered by Junyo and Chiyoda. In fact, it was no coincidence that the only victim of American aircraft that day was Hiyo; for Hiyo was attacked by the only American Avenger squadron lugging torpedoes, Belleau Wood’s Torpedo 24. Although at best two, and likely only one torpedo hit the ship, it sufficed to take the converted liner down. Hiyo was in a turn, trying to evade the bombers which were attacking from above, when she ran afoul of an aerial torpedo. The details of Hiyo’s damage are sketchy, but it may be presumed with some reason that Hiyo was struck on her stern, disabling her steering and stopping her. She sank two hours later, when a tremendous explosion tore her apart, as similar explosions had doomed Shokaku and Taiho before.

But overall, the results of the attack had been meager. Twenty U.S. planes had been lost

in the attack, sinking Hiyo, damaging three other carriers, and crippling two oilers. Now, the American fliers set out for their return flights in the darkness that was settling on the

Philippine Sea.

But overall, the results of the attack had been meager. Twenty U.S. planes had been lost

in the attack, sinking Hiyo, damaging three other carriers, and crippling two oilers. Now, the American fliers set out for their return flights in the darkness that was settling on the

Philippine Sea.

Occasional planes dropped out of formation and ditched far from the Task Force as battle damage made the planes unfit for the longer flight back; but even those planes which were undamaged had no guarantee of returning to the fleet. The closer to the Task Force the strike planes came, the more had to ditch for a lack of fuel. Back aboard the fleet, everything was prepared to make the landings safe. The lights were turned on, as was practice during night landings, but in addition, searchlight beams pierced the skies to form beacons for the returning U.S. planes; night fighters were launched to shepherd in the returning planes; and star shells fired by the 5” guns of cruisers and destroyers made day of the night.

Returning planes started to arrive shortly before 2000 hours, and continued during the evening. The last plane landed on Enterprise at 2210; but the tally was quite disturbing. Of the 215 planes launched, only 115 had returned, some of those damaged. The pilots’ fighting morale by now had hit rock bottom: they were elated to be back, but a mention to them of Mitscher or Spruance did not elicit cheering responses, Mitscher’s decision to use searchlights and star shells for their aid notwithstanding.

Aftermath: June 21st and Epilogue

Night mercifully settled on the battered Mobile Fleet, limping west, licking its wounds from the two-day engagement that had so decisively settled the question on who was the ruling naval power in the Pacific. There was mistaking it: Admiral Ozawa’s retirement, and the decision to abstain from renewing the battle, had ended all hope the Japanese might have had to stem the American tide. There was now only the chance to safe what was left, and Ozawa managed as much: although Spruance detached a force to roam ahead of the carriers and although Avengers sighted Ozawa on the morning of the 21st, no further fighting ensued. Task Force 58 shaped course back to the Marianas, were it remained a short while, then headed for Eniwetok for replenishments and rest. On the 21st and 22nd, and a few days thereafter, American ships and planes rescued 62 airmen from the Philippine Sea; 101 men had already been saved from planes going down near the force. All in all, American losses aboard ship and in planes during the Philippine Sea battle barely numbered 200. Against these must be counted the Japanese lost in Shokaku, Taiho and Hiyo (in each case about two-thirds of the ships’ company) and the oilers destroyed, as well as in the some 400 planes which were lost from the carriers. It was, all in all, a telling count. Not even at the best of its times had the Japanese Navy’s air arm inflicted remotely as severe casualties as the U.S. had over the Philippine Sea. American superiority in radar, in fighter strength and proficiency, and mere numerically advantages made any engagement with the U.S. Navy an almost suicidal matter.