Japan's Decisive Battle

Admiral Yamamoto Isoruku, the short, deep-chested, broad-shouldered Commander-in-Chief

of the Combined Fleet, was as shocked as anybody in the land of the Rising

Sun. It was 18 April 1942, and the Imperial Japanese Navy, chief guardian

of the Empire and the Home Islands, had suffered its most embarrassing

defeat ever. That same day, eighteen B-25 Mitchell medium bombers, lent

from the Army Air Corps, had flown off the deck of the carrier Hornet,

accompanied by Enterprise, at a distance of only 650 nautical miles.

Led by Lt.-Col. James H. Doolittle, these bombers had hit Tokyo, Yokosuka,

and a score of other towns. They had not inflicted material damage that

would have caused military harm, but they had severely shaken the Japanese

morale. If the Americans could hit Tokyo, they could also hit the Emperor's

palace; that the Emperor might be harmed by an air attack was an untenable

situation.

For Yamamoto, this situation was the lever that multiplied his power to

press through his grandiose scheme for the decisive battle. Ever since

the last days of March, he had been pressing hard to convince the

Naval General Staff that the envisioned attacks on Samoa and Fiji Islands

needed to be dropped in favor of an attack on the tiny Central Pacific

island of Midway. The Naval General Staff had bowed to him before

the Doolittle Raid -- but not before Yamamoto threatened his resignation

as Commander-in-Chief. Effectively left without option, the General Staff

had decided in favor of the Admiral, but was not convinced of the scheme

presented to them by the Admiral's subordinates conducting the "negotiations".

Now, it seemed that all objections were swept

aside by the wave of fury rolling over the

country.

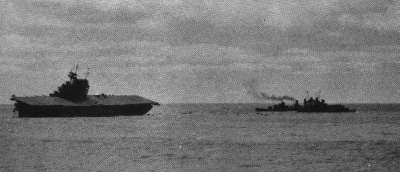

A grand battle scheme was set up by Yamamoto and his staff. The entire force comprising the Combined Fleet would be sent across the Pacific to give battle to the U.S. Pacific Fleet in the waters around Midway. To achieve that goal, Yamamoto's order of battle included virtually every fighting unit that was not needed in secondary tasks around the Empire.

Among them were seven battleships, ten carriers, some two dozen cruisers, and more than seventy destroyers, dispersed among half a dozen fleets. Admiral Yamamoto himself would lead the impressive Main Body, battleships Yamato, Nagato, and Mutsu, the pride of the Imperial Japanese Navy and its most powerful battleships. Support would come from the light carrier Hosho and its eight attack planes, scheduled for anti-submarine work. Destroyers would screen the force.

Then there

was the Aleutians Strike Force, commanded by Vice-Admiral Hosogaya Moshiro,

consisting of a carrier force with the light carrier Ryujo, and

the converted cruise-liner and now-carrier

Junyo. The four battleships Ise, Hyuga, Fuso, and Yamashiro

would be the far-cover for this operation,

and an assortment of cruisers and destroyers would be protecting both forces.

| Admiral Kondo Nobutake would be leading the Second Fleet, including battleships Kongo and Haruna, and the light carrier Zuiho. His task would be to protect the Invasion Force under Rear-Admiral Tanaka Raizo. As with the other forces, a major force of destroyers and cruisers would be available for screening. But the true jewel of the fleet was the fear-imposing First Air Fleet. Under Vice-Admiral Nagumo Chuichi, this force had been the strike group at Pearl Harbor and since then covered every major Japanese operation. For this mission, all six of the heavy carriers would be available according to the plan. Two battleships and two heavy cruisers plus a destroyer squadron would be forming the protective circle around the vulnerable flattops. |

|

Then, with the Main Body, and Kondo's support forces available for battle,

the Japanese would sink the U.S. Navy if it appeared. Before

all this, Yamamoto hoped to reduce the U.S. forces with a tight submarine

cordon, to deploy by 1 June northwest of the Hawaiian Islands. This cordon

would, as pre-war Japanese naval doctrine had predicted, sink as many U.S.

ships as possible, thinning out their ranks before their final engagement

with the Main Body.

This plan was the one presented to the Naval General Staff, and this was

the plan Admiral Nagano, Chief of the Naval General Staff, accepted and

ordered on 5 May.

However, by this time important changes had taken effect. Since the Army was by no means convinced of the decisive nature of the future battle at Midway, it had pursued its own plans. Operation MO, the capture of Tulagi Island and Port Moresby, had been started under the cover of carriers Shokaku and Zuikaku. This was an important splitting of Admiral Nagumo's carrier force, for it risked the availability of a third of the First Air Fleet.

Admiral Yamamoto had allowed these carriers to participate in MO, for he had not expected troubles, believing the Americans to be morally beaten and incapable of mounting an operationoutside his, Yamamoto's, choosing. He was wrong; both Shokaku and Zuikaku, and the light carrier Shoho, were put out of action at the Battle of the Coral Sea, 8 May 1942, by a U.S. force prepositioned thanks to the most important American equalizer of the war - U.S. Intelligence.

U.S. Intelligence

Commander Joseph P. Rochefort was the commander of this equalizer, the

Combat Intelligence Office (OP 20 02), or "Hypo" as it was commonly called.

Leading a team of highly trained professionals in mathematics, communications

and cryptology, Rochefort, sometime after Pearl Harbor, had his mission

changed from trying to decipher the little-used Admiral's Code and started

work on the cracked JN-25, hoping to improve on the 10% of broken messages

that other Navy codebreakers achieved.

"Hypo" soon became the most important producer of decoded material, and Rochefort was a very talented man when it came to examining the value of the intercepted information. His "Hypo" had had little chance to distinguish itself during February and March, when U.S. carriers hit the exposed island positions during the first carrier raids, but by late April, his codebreakers caught bigger fish. Radio messages were intercepted and deciphered indicating Japanese naval operations of large size to begin in the Coral Sea. Admiral Nimitz based his deployments on the information collected by Rochefort and brought the Japanese to battle in the Coral Sea. "Hypo" had had its first important hit.

But seldom do problems come alone. Even while the Japanese and American forces were battling for the Coral Sea, Rochefort's men, noticing a substantial increase in Japanese radio traffic, found that a new operation was being planned, an operation combining all fleet units Japan could muster.

Rochefort's oft-cited problem was that he had no clues to the target of the operation. His ability to put together the big picture helped convince him that the target, codenamed "AF", must be Midway. However, he had yet to convince his superiors at Navy Communications in Washington, D.C., namely Commander John Redman. For the latter was convinced that if any target in the Pacific warranted this fleet, it was Hawaii. Rochefort chose a trick. Utilizing the underwater telephone connection with Midway, he asked that Midway transmit, via uncoded radio traffic, a message saying that the desalination plant was out of order -- which would be a serious matter on a lonely Pacific isle full of men but lacking substantial natural fresh water supplies.

The Japanese swallowed the bait, and when Rochefort's men decoded another

message shortly thereafter, they were pleased to read that "AF has

problems with its de-salting plant". What Rochefort was finally able to

provide Nimitz with was jaw-dropping. First, he knew that the main objective

was Midway, negating Admiral Yamamoto's deception at Dutch Harbor. Second,

he knew of the submarine cordon, allowing him to deploy his forces prior

to its installment, negating another effect of Yamamoto's plan. And third,

he could mass all ships, planes, and defensive measures on and around Midway,

for he need not fear any other operations.

|

By the time of these revelations, Nimitz had more information than

he could possibly use. Enterprise, Hornet, and Yorktown,

since the sinking of Lexington Nimitz's only carriers, were all

out on sea until mid-May. Enterprise and Hornet arrived

earlier than Yorktown, which was still licking her wounds from the

Coral Sea, on 26 May, and brought bad news. Vice-Admiral William F. "Bull"

Halsey, the inspiring, fearless Commander Aircraft Carriers, Pacific Fleet,

was ill with a skin infection and it could not be helped. Halsey was brought

into hospital, where Admiral Nimitz questioned him regarding his replacement.

Without hesitating, Halsey selected Rear-Admiral Raymond A. Spruance, commander

of the cruisers in Halsey's screen, to lead the carriers into the most

fateful battle of U.S. naval history.

Nimitz accepted, unknowingly turning the bad sign of Halsey's illness into a fortune for the United States. Two days later, Admiral Fletcher, aboard the damaged Yorktown, arrived at Pearl Harbor. Being informed quickly about the situation, Fletcher remarked that he estimated Yorktown would be out of action for at least three weeks. But Nimitz could not wait that long. He ordered that every effort be made to put the carrier out again on 30 May, in time to avoid the submarine cordon. With 1,300 men working on her, Yorktown was in for a record repair. In the meantime, what could be done, had been done. Nimitz had ordered Rear-Admiral Robert English, COMSUBPAC, to deploy a submarine cordon of his own west of Midway, and another one north of Hawaii to support a retreating fleet in case of a defeat at Midway. Furthermore, he had transferred almost all available planes to Midway, and was still re-routing new arrivals to the tiny, soon-overcrowded atoll. Finally, on 28 May, Admiral Spruance, in Enterprise, departed with his two carriers. And yet another of Yamamoto's special plans was discovered and prevented. To assure that no enemy carriers would be around Midway, Yamamoto's staff planned a reconnaissance flight of Emily flying boats to Pearl Harbor from Wotje in the Marshall Islands. They would refuel from a modified Japanese submarine at French Frigate Shoals, an atoll more reefs than land. The same kind of mission, albeit ending in an interfering bombardment, had been conducted once already, and the first of these reconnaissance missions had been conducted as well. But U.S. planes had tracked the Japanese reconnaisance unit, and some quick thinking revealed that French Frigate Shoals were the only possible place to refuel a flying boat. When the submarine that was to fuel the Emily that had been ordered to check Pearl Harbor on 1 June arrived at the Shoals, it was disturbed to find them already occupied by a U.S. seaplane tender group. The mission was abandoned. It would have been important enough -- for the day before, Yorktown, and thus the last of the three battle-ready groups, sortied. Though still not 100% ready, Yorktown would be an invaluable addition to the American forces. |

|

The Battle of Midway: 3 June 1942

The Aleutians were definitely not a great place for flight operations,

and Admiral Kakuta Kakuji was to find that out on 3 June. His orders from

Yamamoto were to strike Dutch Harbor, a small harbor installation on northern

side of Unalaska Island, about halfway down the long, curving, rocky, west-pointing

Aleutian chain. To achieve that goal, Kakuta had command over the light

carrier Ryujo, his flagship, and the heavier, converted carrier

Junyo, and 82 planes. Bad weather hampered his operations

since contact with his force had to be maintained yet could not be maintained

- Ryujo, his flagship, seemed alone until well after 0233, his prepared

launching time. Only when Junyo, his second carrier, came in sight

ten minutes later could Kakuta launch the battle's first air strike against

a strategically and tactically minor target. His planes attacked Dutch

Harbor under clear skies and damaged it severely, but to what effect?

There were no U.S. heavy units in Dutch Harbor and, though the base was

well maintained and well equipped, and its damage severe, the entire point

of the operation was lost thanks to U.S. Intelligence.

Worse effects were, however, still to come. A Zero, damaged during the

raid, crashed on a small island not far from Dutch Harbor, killing the

pilot. A Japanese submarine could not locate the slightly damaged plane,

but American ground forces, led by men of the redoubtable Alaskan Scouts

-- an Army-sponsored militia force, all of them natives -- did, revealing

for the first time the negative points of the Zero which eventually resulted

in its defeat.

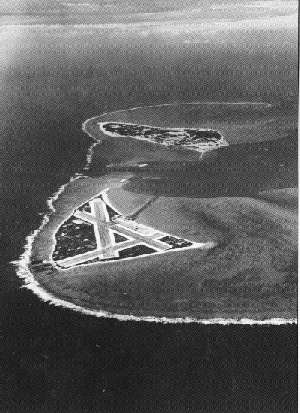

Several hundred kilometers to the south, fifteen minutes after the Japanese

attackers of Dutch Harbor had taken off, the pilots of the search planes

flying from Midway atoll were awakened and got their breakfast, and finally

took off in search of the enemy fleet. Shortly after 9 o'clock, Ensign

Jack Reid of VP-44, flying PBY Catalina flying boats, sighted Rear-Admiral

Tanaka Raizo's Invasion Force.

He radioed the sighting report to Midway, without noting anything but speed

and course. After specifying ship types and numbers on orders from

Midway, giving the base a better picture of the approaching foe, he began

shadowing it for a while. His report enabled a flightof B-17 bombers from

Midway to hit the transport force shortly after half past four in the afternoon.

Without scoring damage, the bombers returned to Midway, and left the scene

for a daring attack by PBYs. Four of the slow, workhorse amphibians took

off from the atoll late in the evening, searching out the enemy transport

force. Finding it an hour after midnight on 4 June, they attacked with

torpedoes and secured a hit on the oiler Akebono Maru, damaging

her slightly, but failing to sink or stop her.

The U.S. carriers had been steaming around north of Midway, waiting for

the enemy to appear, and listening to the action and sighting reports.

Fletcher brought Yorktown closer to Midway in preparation for air

operations. Action was imminent.

4 June 1942

Aboard the magnificent units of the First Air Fleet, preparations for the

air attacks that

morning against Midway

began at 0245 when pilots and aircrews aboard the flagship, Akagi,

were awakened, just fifteen minutes before the

same happened on Midway. By 0430, the first aircraft started lifting off

for their first air strike of the day, 108 planes from all four carriers

this time. Half an hour earlier, PBYs and F4F Wildcat fighters from Midway

had already taken off, patrolling the area and the island.

Scouts were launched from the Japanese carriers prior to the attack, but too few: one Kate each from Akagi and Kaga, supplemented only by two catapult planes from Tone and two from Chikuma, and a smaller scout from Haruna. Besides the mere understrength of this force, Tone's No.4 catapult plane would not launch in time due to a malfunction, and Admiral Nagumo did not send out a replacement as he could easily have done.

The strike, meanwhile, closed on Midway, and appeared shortly before 0600 on the scopes of the Midway-based radar. Midway's base commander immediately launched all available planes, including the twenty-seven fighters led by Marine Major Floyd B. "Red" Parks, which would jump the enemy bombers on their run in. Furthermore, six TBF Avenger torpedo-bombers, four Army B-26 Marauder medium bombers, eleven Marine Vindicator dive bombers and sixteen SBD Dauntlesses, and a total of nineteen B-17 bombers, augmented the rest of the 32 available Catalinas.

Major Park's pilots had a very bad day. Their planes were throughly inadequate in both numbers and quality, engaged the enemy too early, and failed to get into the bombers quickly, owing to the escorting Zero fighters. Of those intercepting fighters, fifteen were shot down, and they were unable to protect Midway from air attack, which task was now left to the air defence units. Total Japanese losses over Midway and before were around fifteen planes shot down and thirty-two damaged. In exchange, the Japanese, without any planes on the ground to strafe or bomb, hit the facilities on Sand and Easter Islands , and left both islands on fire, having destroyed fuel tanks, the hospital, storehouses, and seaplane facilities.

Even before the Japanese planes attacked Midway, however, Nagumo's carriers lost their most important defence when they were spotted by Lt. Howard Ady, piloting a PBY. Ady immediately broadcast the sighting report, which was intercepted at 0553 by Enterprise, Yorktown, and Hypo back at Pearl Harbor. Given another reason for immediate scramble, Midway's planes took off with orders to attack the enemy carriers. The U.S. flattops waited on, but Nagumo's carriers would see their very first action.

Lt. Langdon K. Fieberling led the six Avengers of VT-8, re-routed to Midway

when they had

been unable to catch up

with their mothership, Hornet, and four B-26 Marauder bombers, into

the fray of AA and fighters as the

first U.S. attack group. Above them, old Vindicator dive bombers,

SDB Dauntlesses, and B-17 level bombers approached

for their attacks.

Fieberling's planes attacked first at 0700, but there was no way around

the Zero fighters,

much less one through them.

Four Avengers fell even before they were able to release their torpedoes.

The other planes continued, but three more fell to AA, and the rest, an

Avenger and two Marauders, scoring

no hits and damaged, retired to Midway.

Nagumo, watching the attack from his flagship's bridge, was not too impressed with theability of these pilots, but he felt that they might indeed prove what Lt. Tomonaga Joichi of the Midway strike force had stated: a second attack would be necessary.

In the meantime, unknown to Nagumo, his fate was being sealed. Admiral Spruance, his flagship Enterprise having intercepted the report from Ady, had been steaming toward the enemy to reduce the range. However, when the Japanese planes left the air space over Midway at around 7 o'clock, quick calculations made it clear that if the U.S. carriers launched immediately, they would probably hit the Japanese carriers with planes loaded on the deck, a most vulnerable condition. Accordingly, both carriers launched their planes between 0700 and 0755, full deckloads of bombers with a fighter escort. Twenty minutes past seven, Spruance ordered the new Rear-Admiral Mitscher to take Hornet and an escort and maneuver independently.

Nagumo's ships underwent more attacks in rapid succession -- first Major Loften Henderson's Marine Dauntlesses, then B-17s from the Army, and finally the Vindicators. None scored a single hit, but the more of these planes that attacked, the more convinced was Nagumo that a second strike was indeed needed against Midway. Already at 0715, Nagumo had ordered to arm his ready planes with bombs instead of torpedoes. But by 0730, Tone's No. 4 scout had radioed Nagumo that there were "ten enemy surface ships" in the vicinity. Though worried about the unplanned presence of this force, Nagumo regarded the Midway forces as the main threat and continued the re-arming.

Nagumo was greatly hampered by the incapable aircrew of Tone No.4, which took an hour to find out what it had really sighted: the Yorktown group. Only by 0820 did the plane inform Nagumo that the force included "what appears to be a carrier." Nagumo now had to worry, but didn't for too long, and soon ordered armament changed back to torpedoes. Only half of the Japanese planes were affected, for only half of them had been loaded with bombs after the first of Nagumo's re-arm orders had been given. Due to the time pressure, however, bombs were not being properly stored. The Japanese carriers slowly became floating, unprotected arsenals.

By 0830, the final Midway-based attack against Nagumo's forces had been made, and a mere nine minutes later, Lt. Tomonaga's Midway group arrived overhead and commenced landing. Though interrupted once by a false report of U.S. torpedo planes, Nagumo successfully landed Tomonaga's group, and turned his forces toward the enemy by 0917. Only a minute later, however, Nagumo saw himself faced once again with enemy torpedo planes, for which the Japanese, given their own excellence in torpedo bombing, entertained a healthy respect.

It was VT-8 from Hornet, under the command of Lt.Cmdr. John C. Waldron. His planes were old, slow and sluggish TBD Devastators, once the finest plane in the fleet but, after only seven years' service, it had become an obsolescent deathtrap. Nevertheless, Waldron had trained his pilots to the last -- and, before the battle, suggested to them that they should write a letter to their families.

Now, this brave but hopelessly outnumbered force approached Admiral

Nagumo's carriers. Zeros

were soon between them, and not one Devastator survived the

massacre, as they approached

in the "low and slow" manner necessary for them to conduct a successful

attack, an approach forced upon the

men by their torpedo load, the Mk13. Only one

of the pilots, Ensign George Gay, survived,

and was picked up alive by a PBY the next day.

|

Supported by his lifevest, from his ringside "seat", Gay was able to

watch another torpedo squadron, Lt.Cmdr. Eugene

Lindsey's VT-6 from Enterprise, make

its run in. His fourteen planes were

flown by highly experienced pilots

- Hornet's pilots had been trained but never seen combat,

while VT-6 was a veteran

of the early Fast Carrier raids. Now, Lindsey's force came in right

toward the enemy carriers, and

they soon selected the Kaga

as their prospective prey.

The big flattop fought them off pretty well, assisted by the Zeros of the combat air patrol, and was unhit in the end. This time, ten Devastators had fallen into the sea, including Lindsey's. The engagement was not over for a minute when Akagi spotted another torpedo squadron coming in, this time VT-3 from Yorktown, under the command of Lt. Cmdr. Lance Massey, the only squadron that had a fighter cover with it, Lt.Cmdr. Jimmy Thatch's six F4F-4 Wildcats, and was as combat ready as humanly possible. Neither was enough to protect these last brave torpedo-bomber pilots of the battle. Soryu's Zeros ignored Thatch, pretty much caught up in a dogfight with other Zeros, and headed for the Devastators, and soon, more of the Zeros came in after Massey. Massey's fliers concentrated on Hiryu, but missed — only two planes returned to the U.S. fleet. |

Quickly assessing the situation, McCluskey divided his force into the two

elements, ordering Lt. Richard Best

of VB-6 to strike the right-hand carrier, Akagi, while he himself

led Lt. Earl Gallaher's VS-6 down on Kaga. The Japanese were rather

unimpressed. They had seen these numbers of dive

bombers before and had not been hit. Their own reliance on torpedo bombers

gave them the feeling that dive bombers

were no tool to sink major warships.

A Time Magazine impression of the dive-bombing of Soryu. Since there were few photos that could capture the battles completely, Time built, in an old storage building, a large model with planes, ships, and islands, and photographed these in battle-like poses. |

It

was a fatal error of judgement. American airmen had been among the earliest

promoters of dive bombing as a tactic, and as aircraft began to be radically

improved in the 1930s, though the Army Air Corps did not emphasise it,

the Navy had taken it up as a distinct policy. For years, dive bomber pilots

of the "brownshoe Navy" — so-named because their early flying uniforms

were derived from the Marine green service dress, which required brown

shoes — had taken particular pride in being able to hit their targets,

and partook of fierce inter-squadron and inter-ship competitions, for the

most valuable prize of all — bragging rights. And before them now was something

to really later brag about.

Meantime, the Japanese carriers were not warships at this moment; they

were floating arsenals. Bombs were lying around, and armed and fueled planes

were in place for Nagumo's strike against the enemy fleet.

|

Akagi was not hit by as many bombs, but the results were equally terrifying. The first bomb struck the carrier on the midship elevator, exploding improperly stored ammunition, dooming the ship. The second and last bomb struck the planes being rearmed, detonating whatever ammunition was on them. The aft magazines could not be flooded, and even CO2 could not extinguish the hangar deck fires. The engines died at 1040, and Admiral Nagumo left his blazing command at 1046. Abandon ship was sounded at 1900, although few personnel remained after earlier transfers, and Captain Aoki was removed from the carrier as, presumably, the last living individual at 0300 on 5 June.

Soryu's story was different only so far as her hunters were from a different carrier. Lt. Cmdr. Maxwell Leslie of Yorktown, leading VB-3, was somewhat ill-fated during the approach. His SBDs were equipped with what a computer user would call a "buggy" electronic arming mechanism, resulting in the loss of his bomb and that of three of his compatriots. With only thirteen bombs, the flight continued, but it was not to be the bad omen it could have been. Leslie's gunner sighted the Carrier Force at 1005, and Leslie quickly chose a large carrier he identified as Kaga as his unit's target. It was actually the smaller Soryu but a nice prize nevertheless. Leslie dove down on the carrier ahead of his squadron at around 1025, raking the AA emplacements and the flight-deck with his forward-mounted .50 caliber guns -- his only means of attack until they jammed. Soryu was struck by three bombs, neatly placed from fore toaft, exploding near all elevators, destroying all planes and ammunition stored on and beside the planes, and was out of the action by 1040, ten minutes after the last Yorktown planes had pulled up. Five minutes later, abandon ship was sounded, and Captain Yanagimo to committed suicide by plunging into the raging fires. Attempts to keep her afloat were made, but shortly after 1920, she finally slid into her watery grave.

However, victory was not complete. Rear-Admiral Yamaguchi Tamon, COMCARDIV2, had seen his command reduced to half with the hits on Soryu, and was determined to pay it back to the U.S. His ship, Hiryu, was completely intact except for the losses her air group had taken in the attack on Midway. Hiryu had become separated from the rest of the fleet during the torpedo attacks, and anyway, no planes would have been available to hit her. Now, Hiryu and her fighting admiral assumed virtual command over the rest of the force.

Actually, Rear-Admiral Abe Hiroaki, commander of Nagumo's screen, was the

senior officer present, and he issued,

at 1050, Yamaguchi his orders: attack the enemy carrier -- Immediately!

Lt. Kobayashi Michio took off at the head of eighteen dive bombers and

six fighters, trailing the Yorktown group, and at 1140, Japanese

fliers sighted TF17, while Yorktown's radar located the incoming

strike. Yorktown's condition was completely different from the Japanese

carriers. No ammo was lying around,

no fueled planes aboard her, besides the immediately scrambling fighters

-- even her aviation fuel lines were secured by the use of CO2 in them.

|

Fighters jumped the enemy planes fifteen miles out, and eight Vals, as

the Allies called the Aichi D3A dive bomber, fell, along with two more

to the thick flak fire. But eight penetrated, including Kobayashi's

plane, scoring an impressive three hits. Although no immediate danger to

the carrier resulted, her speed was temporarily reduced to a mere six knots.

Once again, Yorktown's crack damage control parties saved

their ship, soon bringing her up to 20 knots.

Fighters were landed, and a new combat air patrol launched. But Yorktown, as the only target for Yamaguchi's bombers, was not spared a second attack. This time it was a flight of ten Kate torpedo planes, which, due to space and time restrictions, had not been able to take part in the first attack. Captain Elliott Buckmaster, a good positive score on his side in the Coral Sea battle, where he had successfully evaded all torpedoes, was now faced with a grim situation he could not master. Two torpedoes (six torpedo-planes had been lost on the approach despite a six plane escort) struck Yorktown, and her increasing list, seemingly unstoppable, left Buckmaster with no choice but to abandon his ship. At 1500, he ordered the crew to do just that. Yorktown would be left on her own. |

|

5-6 June 1942

The coming of the evening of 4 June saw five carriers bobbing, four

burning, and all abandoned. But while the Japanese carriers were clearly

unsalvageable, Yorktown was not.

Fletcher, now aboard the heavy cruiser Astoria, had set off to join

Spruance, but the destroyer Hughes

remained near the carrier and reported that chances were she could be saved.

Fletcher ordered the tug Vireo from French Frigate Shoals to tow

her to Pearl, later joined by destroyer Gwin, and sent three more

destroyers from the screen around Enterprise to get a salvage party

aboard the ship. Captain Buckmaster was with these men as they boarded

Yorktown, and slowly, the carrier was towed toward Pearl Harbor.

She was not to make it.

Admiral Yamamoto had ordered the submarine I-168 to go after the carrier, and it did, sinking it under of the protection of four destroyers as well as the destroyer Hammann alongside her. The 5th of June was the day of the submarine, indeed. Admiral Yamamoto, in a rather foolish attempt to gain at least something, ordered Admiral Kondo to bombard Midway. Admiral Kondo in turn gave the same order to Admiral Kurita Takeo, commanding the youngest and fastest cruiser division in the IJN. These ships, however, had not yet reached Midway when, at 0020, Yamamoto's order to turn back was received, and as they complied, they maneuvered themselves into more trouble. The U.S. submarine Tambor had sighted them earlier, and shortly after 0100, a submarine was sighted by Kurita's Kumano, which Kurita tried to evade by an emergency simultaneous turn by 45 degrees of all his cruisers. But while executing this maneuver, Mogami and Mikuma, two of his heavy cruisers, collided.

At daybreak, the two cruisers were protected by two destroyers, slowly making way out of Midway's range. But they were too slow, and Kurita's order to have Mikuma stand by her sister now endangered both vessels. Midway SBDs and Vindicators began their attacks at 0745, scoring no hits, but probably a plane crashed on Mikuma. B-17s followed, scoring nothing, but the heavy cruisers were slowed down. By the next day, planes from Enterprise and Hornet found the enemy and struck repeatedly, sinking Mikuma and knocking Mogami out of the war for a year.

Over 5 and 6 June, Yamamoto had pondered about committing his remaining forces to a night surface action but had dropped this idea for fear of the risk he would be running. Rightly so: Admiral Spruance, whom Fletcher had given command after the loss of Yorktown, headed east in the night, knowing that a night surface battle -- any surface battle -- was not recommended.

Yamamoto's fleet retired. Attu and Kiska had been taken, but at what cost!

Four heavy carriers, one heavy cruiser,

one hundred pilots, 3,400 sailors, three experienced carrier skippers and

a carrier admiral, plus the secrets of the Zero fighter. In exchange, the

IJN had sunk a carrier and a destroyer, and destroyed around 150 planes.

It was nothing short of a disaster into which Yamamoto had led his fleet,

and he was only right in claiming responsibility for this operation and

its losses. Both fleets returned to their ports to think about their lessons

at Midway.

History's greatest naval battle was over. The United States had won.

Epilogue

The Battle of Midway was the most decisive single naval battle in U.S.

history. The battle left

two heavy Japanese carriers

against four U.S. carriers, and cost the Japanese veteran pilots whose

inexperienced replacements would require a full year of training.

Furthermore, the Imperial Japanese Navy lost the secret of its Zero fighter,

leading to certain improvements of the F6F Hellcat, which would, just a

year later, begin to destroy Japanese air supremacy.

The Battle of Midway enabled the U.S. Navy to go onto the offensive. Herein

lay the importance of the battle. For

this is where I think people are wrong when they say that the loss of the

battle would not have been a too important

event. If the U.S. had indeed lost all three carriers at Midway

there would have been merely three carriers remaining to oppose any

Japanese move -- none of which was a really good ship. Saratoga

was old and slow in maneuvering, Wasp small and with a small complement

of planes, and Ranger slow and small as well as ill-protected. None

of these carriers could hope to last

in a battle with the Japanese carrier fleet which would allow the

Japanese to prosecute several goals: construction

of airfields on Guadalcanal; invasion of Port Moresby;

invasion of New Caledonia; and more. The Battle of Midway reversed this.

The Japanese could never again operate offensively, while the Americans

could now do so at places of their own choosing.

Detailed

OOB United States

Detailed

OOB Japan

These OOBs are courtesy

of Mr. Philipp Windell.

|

|

|

| Carrier Strike Force

(Admiral Nagumo): CV Akagi (+) CV Kaga (+) CV Hiryu (+) CV Soryu (+) 2 Battleships 2 Heavy Cruisers 1 Light cruiser 11 Destroyers |

TF-16

(Admiral Raymond Spruance): CV-6 Enterprise CV-8 Hornet 5 Heavy Cruisers 1 Light Cruiser 9 Destroyers |

| Close Support, Midway

Bombardment Group

(Admiral Kurita) CA Kumano CA Suzuya CA Mogami (O*) CA Mikuma (+) |

TF-17

(Admiral Frank Fletcher): CV-5 Yorktown (+) 2 Heavy Cruisers 6 Destroyers (Hammann +) |