I believe that there were four stages that the prisoners were exposed to. The first stage is the capture or surrender of the person or persons.

The second stage is the treatment of the men and women while in a Japanese prison or work camp. The third stage is the transfer by forced march or

transport to other camps or to the Japanese homeland. The fourth and final stage is the rescue and return to the American way of life.

The history of the first three stages is well covered by many books. I concentrated on three. WITH ONLY THE WILL TO LIVE, edited by Robert S.

LaPorte, Ronald E. Marcello and Richard L. Himmell; PRISONERS OF THE JAPANESE by Gavan Daws; and The Shinyo Maru Survivors Reunion, 7 September

1998 at San Antonio,Texas Booklet. These books describe the life of the prisoners and the brutal treatment, as they were used as slave labor, and

their constant battle with hunger and disease. I will cover very little of this history. Stage 3, the transportation of the prisoners, from camp to camp

and to Japan via Japanese transports, is well covered by the book Death on the HELLSHIPS, by F. Michno and others.1

In the fourth stage, I will attempt to list the names and some history of the Prisoners of War that were on the Shinyo Maru, when the USS

Paddle, SS 263 sunk the ship in 1944. Some of these men swam 3 or 4 miles to a nearby island and later were evacuated by the USS Narwhal,

SS 167.

"The Japanese were not directly genocidal in their POW camps. They did not herd their white prisoners into gas chambers and burn their corps in ovens.

But they drove them toward mass death just the same. They beat them until they fell, then beat them for falling, beat them until they bled, then beat

them for bleeding. They denied them medical treatment. They starved them. When the International Red Cross sent food and medicine, the Japanese looted

the shipments. They sacrificed prisoners in medical experiments. They watched them die by the tens of thousands from diseases of malnutrition like

beriberi, pellagra and scurvy and from epidemic tropical diseases: malaria, dysentery, tropical ulcers, and cholera. Those who survived could only look

ahead to being worked to death. If the war had lasted another year, there would not have been a POW left alive."2

"In a Japanese prison camp, under guards holding life-or-death power, what was it going to take to stay alive, stay sane, stay human? When a body is

savagely beaten, what happens to the mind and to the spirit? Among starving men, can common human decency survive? What is the calorie count on friendship,

on personal loyalty, on moral agreements, on altruism? In prison camp, what would it mean to say that a man is his brother's keeper?"3

"Every POW saw men like himself die horribly. Every POW saw men like himself offer themselves up to death so that others might live. Those who survived

had to struggle to keep themselves alive in the camp, and then struggle to live with themselves, back in the world; they were branded by the experience.

They have borne the tribal scars of the POW ever since."4

"Now we come to the movement of the POWs from camp to camp or the homeland of Japan to work as slaves. The Japanese state that about twenty-five ships

carrying POWs, from various nations, were either bombed or torpedoed. These ships were not marked in any way to designate them as transporting POWs. The

Japanese put them in a convoy as any other ship. Without markings, the U. S. Submarine Captain assumed that he had a prime target.

"According to Japanese figures, of the 50,000 POWs they shipped, 10,800 died at sea. Going by Allied figures more Americans died in the sinking of the

Arisan Maru than died in the weeks of the death march out of Bataan, or in the months at Camp O'Donnell, which were the two worst sustained

atrocities committed by the Japanese against the Americans. More Dutchmen died in the sinking of the Jun'yo Maru than in a year on the Burma-Siam railroad.

The total deaths of all nationalities on the railroad added up to the war's biggest sustained Japanese atrocity against Allied POWs. Total deaths of all

nationalities at sea were second in number only to total deaths on the railroad. Of all POWs who died in the Pacific war, one in every three was killed in

the water or by friendly fire."5

Naturally the prisoners did not know anything about what was happening on the open seas. The Japanese were still loading the prisoners, into unmarked

transports, so that they could be shipped to another camp or to Japan. Without the knowledge that the transports were carrying POWs, the submarine Captains

and the Bombers continued the sinking until there was nothing to sink.

So the POWs, who suffered so much on land, suffered again at sea. They died in the holds, of starvation, suffocation, dehydration, and disease and with

no sanitation. They were killed by bombs and torpedoes aimed at them by the allies, their countrymen. When the men tried to leave the sinking ship, the

Japanese fired on them or threw hand grenades at them. If anyone was lucky enough to survive this the Japanese in lifeboats would kill them in the water,

or they drowned, or they died on the rafts. Or, most terrible of all they killed each other.

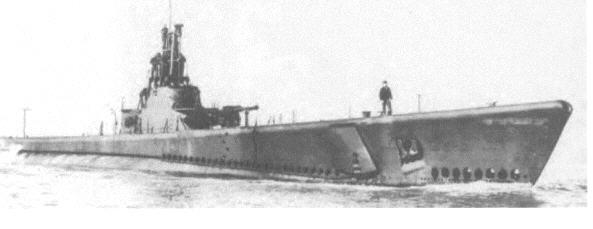

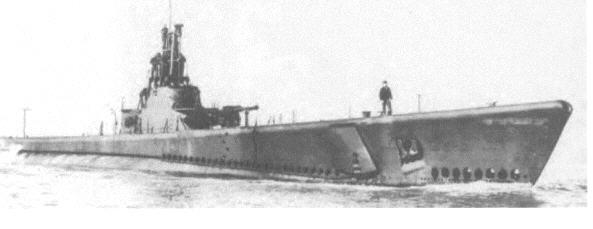

Now we come to the action of the USS Paddle, SS 263, on her fifth war patrol. The Paddle after her fourth war patrol had her refit at

Fremantle, Australia. Her fifth patrol was scheduled from 22 August -25 September 1944.

"While in her patrol area, about ten miles north of Sindangan Point, Mindanao, she sighted a small convoy. The convoy was made up of a medium tanker,

two medium AK's, two small AK's, two torpedo boats or DE type escorts and one small coastal tanker type craft. There were two planes overhead. The tanker

was a medium sized modern vessel half loaded. The two AK's were new looking ships with two single stack masts, one fairly low stack. ALL VESSELS DID NOT

SHOW ANY UNUSUAL MARKINGS. No identification as to name was attempted because all periscope observations were very brief with flat calm sea prevailing.

Four torpedoes were fired at the tanker with two hits. Two were fired at the leading AK, the boat had to dive deep as the escorts turned toward the boat.

Damage to the tanker and AK could not be seen. However, loud, characteristic, breaking up noises were heard almost immediately and continued on for

sometime after the depth charging started. Commenced taking a total of 45 depth charges and bombs, none close enough to do any major damage, but jarring

the boat considerably. No. 43 was very close. The attack lasted about two hours and then the boat came to periscope depth and started patrolling again."6

"While in her patrol area, about ten miles north of Sindangan Point, Mindanao, she sighted a small convoy. The convoy was made up of a medium tanker,

two medium AK's, two small AK's, two torpedo boats or DE type escorts and one small coastal tanker type craft. There were two planes overhead. The tanker

was a medium sized modern vessel half loaded. The two AK's were new looking ships with two single stack masts, one fairly low stack. ALL VESSELS DID NOT

SHOW ANY UNUSUAL MARKINGS. No identification as to name was attempted because all periscope observations were very brief with flat calm sea prevailing.

Four torpedoes were fired at the tanker with two hits. Two were fired at the leading AK, the boat had to dive deep as the escorts turned toward the boat.

Damage to the tanker and AK could not be seen. However, loud, characteristic, breaking up noises were heard almost immediately and continued on for

sometime after the depth charging started. Commenced taking a total of 45 depth charges and bombs, none close enough to do any major damage, but jarring

the boat considerably. No. 43 was very close. The attack lasted about two hours and then the boat came to periscope depth and started patrolling again."6

I was able to contact a shipmate who was a crewmember of USS Paddle on her fifth war patrol, Godfrey J. Orbeck., CPhM. This is his recollection

of this action. "We attacked a convoy about a mile or two off Sindangan Point, Mindanao on 7-8 September 1944. We got two torpedo hits on the lead ship, a

tanker and two hits on the second ship in the column. We the crew of Paddle [SS 263] were unaware that the Shinyo Maru was carrying POWs

[750 of them] until after the war. The escorts, the Captain identified one of them as a Q ship were dropping depth charges immediately.

"The Skipper ordered deep submergence immediately, but we were light forward, due to the departure of four fish from the forward room. The Skipper

ordered all hands, those not engaged in ship's tasks, to the forward torpedo room since we could not use the trim pump at that time.

"By the time I got to the forward room, the men of the crew occupied most of the space. I crawled over several men got an unused torpedo skid, which I

laid on and later went to sleep. I was standing night watches in the conning tower from midnight to sunrise so day time hours was sleeping time for me.

"The Skipper of the tanker ran his ship up on the beach to keep her from sinking. They had a machine gun on the stern, which was manned by a Jap gunner

who was shooting at the heads of the U. S. Prisoners in the water. Japs in the lifeboats were also shooting at the POWs and would not permit U. S.

personnel to get aboard the lifeboats.

"Paddle stayed deep until the depth charging was over, then we surfaced, reloaded tubes and put in a battery charge. Paddle proceeded

northward along the coast looking for the tanker. We were unaware that she had been beached. We had heard breaking up noises from only one ship, the

Shinyo Maru. The Skipper wanted to finish off the tanker."7

Unknown to us, 83 POWs made it to the beach. One died on the beach. "The 83rd man was known as Tennessee. But no one seems know to what his real name was.

He died about two days after we came ashore, and was buried on the hill in back of the town Sindangan."8 So

there were only 82 survivors. The Paddle crew did not find out about the POWs until after the war. The skipper told Orbeck, that he did not learn

about the POWs until he went to the Bureau [of Navigation, Ed.] to check on his orders in 1946.

Unknown to us, 83 POWs made it to the beach. One died on the beach. "The 83rd man was known as Tennessee. But no one seems know to what his real name was.

He died about two days after we came ashore, and was buried on the hill in back of the town Sindangan."8 So

there were only 82 survivors. The Paddle crew did not find out about the POWs until after the war. The skipper told Orbeck, that he did not learn

about the POWs until he went to the Bureau [of Navigation, Ed.] to check on his orders in 1946.

Friendly Filipinos helped the 82 survivors. Most all were clothed only with a G-string. Within a few days the survivors made it inland to a guerilla

group, back in the jungle commanded by a U. S. Colonel named McGee. General McGee had been a member of a POW group, some weeks earlier, but escaped and

formed the guerilla group in the jungle. General McGee's group had sent a radio message to the U. S. forces in the south about the 82 survivors. The USS

Narwhal, SS 167, was assigned to pick up these men."9

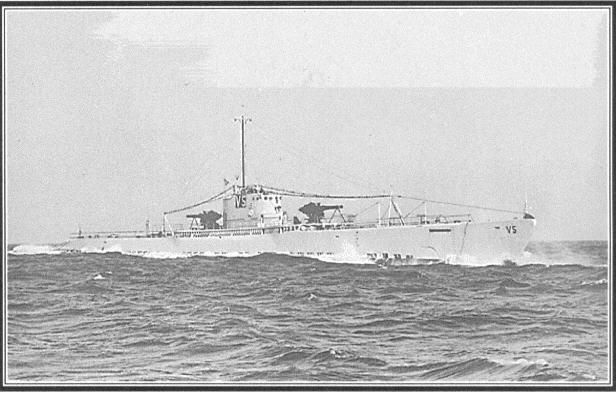

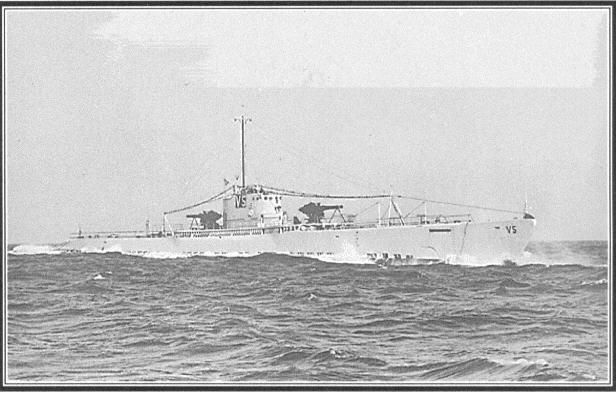

The USS Narwhal, [V 5] SS 167, under the command of Commander Jack C. Titus, departed on her fourteenth war patrol on 14 September-5 October 1944.

On the 27th of October she deposited men and stores on the island of Cebu. She then took off and on the 29th picked up the 81 surviving POWs from the

sinking of the Japanese AK by the USS Paddle. "The Narwhal after seeing security signals. Surfaced with small boat in sight flying U. S.

Ensign. Captain Thomas, A.U.S. [the representative of the area commander] came on board. At his request moved into Siari Bay. This is a poor location due

to currents, shoal water and lack of protection. This is probably the first day in the past five that boating would have been feasible here, with

conditions almost perfect for this season. Recommend the eastern side of Sindangan Point for future operations. Boats alongside. Put two rubber boats in

the watered manned by reliable petty officers to bring back stretcher cases, 81 survivors and 1 doctor on board. These survivors were prisoners of war

being moved north from Davao when the transports were torpedoed about 6 September. Four of them were stretcher cases. Gave shore party flour, coffee and

lubricating oil. Took on board official mail. Backing Clear. Made trim dive."10

As noted there were only eighty-three POWs that were capable of swimming or by whatever means were capable to land on the beach. It was with great

sorry that one of their members, John J. McGee, died shortly after reaching the beach. Of the remaining eighty-two, eighty-one were rescued, one member

namely, Joseph P. Coe refused to be picked up. His son-in law Joseph M. Meehan provided this information:

"My father-in-law, Joseph P. Coe Jr., was on the Shinyo Maru when it was sunk on Sept. 7, 1944. He escaped and made it to shore. He later refused

to be picked up with the other survivors and stayed on Mindanao and served as a radio operator under the command of Brig. General Wendall Fertig. For this

he was later awarded the Bronze Star. He continued in the U. S. Army, after the war, serving in both Korea and Viet Nam, and retired in 1976 as a Colonel.

His last assignment was as the commander of the Signal Corp Battalion at Ft. Huachuca, Arizona. He died in 1977, I did an oral history interview with him a

few years before his death and I am working on compiling a history of his military career."12

This is a Biographic Sketch of another survivor, namely, Theodore L. Pflueger.

"I am a member of ADBC, Inc., No. 3456. I am also a life member of EX-POW, Card No. 15930. I was in the 809th Avn Co. in September 1941 when I came to the

Philippines, and was stationed at Nichols Field. The Company later became "C" Co., 803 Avn Engr Bn the week before the war started. I was promoted to 1st

Lt. In the Corps of Engineers the month of November 1941

"I was on the Death March and started from about Kilometer 210 down to Marvelis and from there to San Fernando Pampanga, where I boarded a cattle car,

packed in like sardines to Capiz and thence to O'Donnell, Marvelies. I was trucked from O'Donnell to Camp 3, Cabanatuan, and later to Davao Penal Colony

[Dapecol] Camp on Mindanao. Later transferred to the Airfield at Lasang; at Zamboanga, about 3 September 1944 I was transferred to the hold of the ship

Shinyo Maru.

"The US Submarine Paddle sank this Hell Ship on 7 September 1944 in Sindangin Bay, Mindinao, PI. Most of the [about] 800 POWs died when the 2

torpedoes went off in the holds where we were packed, and the Japanese shot the rest in the water as we were swimming away from the sinking ship. All that

was left of about 800 POWs that had been on the unmarked ship were 83 men who managed to reach the shore near Saindangin and one man died the next day,

leaving 82 survivors.

"I was able to leave the Philippines by way of the USS Narwhal, and eventually wound up in Brisbane, Australia in the Army Hospital there,

along with other survivors of the sinking Shinyo Maru. I have a complete list of the 82 survivors, [ I am one of them ] and there are 25 of these

men alive today. Contact me if you want any information from my list. "Ted" Pflueger"13

My last POW covered will be Onnie Clem. I feel that his actions and reactions were typical of each prisoner. The information about Clem is taken from

the book WITH ONLY THE WILL TO LIVE.:

"Onnie Clem of Texas, was a Sergeant in the U. S. Marine Corps, 3rd BAT. 4TH REG., at Cavite Yard. Captured on Bataan and spent time at 1-Camp O'Donnell,

2-Cabanatuan and 3-Davao Penal Colony. Clem was on board one of the infamous Death Ships when it was torpedoed a couple of miles outside Zamboanga,

Mindanao. He swam ashore, was found by Filipino guerrillas, and ultimately was evacuated by an American submarine."

Clem narrated the following: "The Japanese put 250 of us in this forward hold. And in the after hold they put another 500 men. The ship would travel a

little ways and stop; it might stop several hours and start up again. We were aboard this ship altogether about nineteen days and eighteen nights. You had

room to sit and lay down; the food was a little better. Well, late one afternoon we heard the Japanese bugler blowing general quarters, and in the process

of blowing it he trailed off. He just pooped out, hit some sour notes. Suddenly the Japanese pulled the hatch covers off and dropped hand grenades down in

there and then turned machine guns down the hold. Well just about the time they started that, there was this explosion. What had happened was that a

torpedo had hit the ship. Personally, the only thing that I remember was that I saw a flash, and everything turned an orangish-colored red. No feeling, no

nothing. Every-thing just turned a solid color. I don't know if the grenades went off first or the torpedo because it all meshed together. As I said,

everything turned red on me, and I assume that's when the torpedo hit. The next thing I knew, I was kind of flying, just twisting and turning, and there

were clouds of smoke all around me. I couldn't see anything but these billowy forms like pillows. I thought I was dead.

"Then I opened my eyes, and reality came back. I was underwater in the hold of this ship, and these pillows were the bodies of other guys in there. Some

of them dead; some of them were trying to get out. The ship was filling up with water, and I thought it had already sunk; and I thought I was trapped down

in it, and I thought I was going to die, sure enough. So I figured the quickest way to get it over with was to go ahead and drown myself. So I opened my

mouth and thought I'd drink some water.

"I found that my head was above water, and I was just gulping air. I looked up, and I could see light coming through this open hatch. Then I thought,

'Well , I can get out of here.' In the meantime, all this water was rushing up toward this hatch, and the ship was filling up and sinking. I had actually

been forced into a corner and was away from the hatch, and this was one place where it was everybody for themselves-survival of the fittest. Everybody was

clawing at each other trying to get to the hatch. You'd pull one person out of the way to get a little closer to the hatch. I finally reached the hatch,

and two other guys and I pulled ourselves out at the same time.

"Up on the bridge there was a machine gun spraying the hatch. A burst of machine-gun fire caught all three of us and knocked us back down in the hold.

We'd all been hit. I got plowed in the skull. Another bullet chipped out my chin. Nevertheless, I was able to work myself back up on deck, and I was eyeing

that bridge when I came out that time. The gun was still there, but the gunner was laying out on deck. Somebody had apparently got up there and killed him.

At this time I found out that we were out in the ocean about two or three miles from shore. All I had was a loincloth.

"All I could think of was getting to that land and getting some water or coconut milk. I couldn't see out of one eye on account of the blood. I'd reach

up there, and I knew I was shot. I figured I was in pretty bad shape, buy I still wanted to get to shore and get something to drink. You could barely see

the land. So the first thing I thought of was that I had a long swim. I pulled off my loincloth so that I had nothing to encumber me in swimming. Also, I

had been down in the hold for nineteen days and eighteen nights, so I didn't have a lot of strength. Anyway I dove over the side, and when I hit the water

I happened to look up, saw that we were part of a convoy because there were many ships around. The other ships had putout lifeboats to pick up Japanese,

but they were shooting all the Americans. They were shooting them, or some of the officers were taking swipes at their heads with sabers. There were Japs

all around me. Hell, there were lots of Jap troops on this ship.

"Then there was a seaplane patrolling for this convoy, and we had to contend with him. He'd make a pass and strafe us. In the meantime, I couldn't hear

a thing because, I found out later, both my eardrums had been perforated in the concussion of the explosion. I was as deaf as I could be, so in the swimming

all I could sense was little shocks in the water, and I didn't know what it was. I'd look around and the water would be spraying up, and it was where

somebody was shooting. We swam and we swam, and my right arm just finally got to where I couldn't swim, I couldn't move it, couldn't pull it over my head.

It was completely paralyzed, useless. I found out later that while I had been swimming I'd been shot twice-once in the arm and once in the shoulder. We got

to the beach a little before sundown. Two of us got into some trees off the beach, and a Filipino walked up. He had on a pair of cut-off dungarees, and he

took them off and gave them to me, and then he climbed up this coconut tree and got a bunch of coconuts and cut them down for us.

"We walked about a mile inland and came upon this hut with several Filipinos standing around. They gave us some water-I never could get enough water-and

then they took us to a village probably five or six miles away. Then they started to bring other Americans into this village. We stayed there that night,

and there were eighty-three of us that showed up. There were 750 of us on that ship, and only eighty-three of us got ashore...

"They moved us into a main guerrilla camp about ten miles back in the hills. They took the slugs out of my arm, but they never did take the one out of

my back. This guerrilla encampment had radio contact with Australia, and they promised us that the next time they brought in supplies by submarine they

would take out the wounded. We were supposed to be down at the beach at a certain time. One night after we'd been with the guerrillas about a month

we went down to the beach and this submarine surfaced and the Filipinos took us out to the sub in dugout canoes."14

It should be noted that these POWs have had reunions. "Their last one was in San Antonio, Texas on 7 September 1998. There were seventeen present.

Some were in no condition to travel, one died in a car accident on his way to the reunion, and some felt that it was too far to travel. There were

seventeen members and others in attendance, wives and children of the attendees, and one of the men from the USS Paddle, Godfrey J. Orbeck CPhM, the

submarine that sunk the Shinyo Maru. One of the widows was there, Peter Golino's wife. One woman who was the daughter of the Camp Commander at

Lasang, our last POW camp. Plus there were a few others that wanted to visit with us because they had relatives that were on the Shinyo Maru and went down

with the ship. They had a welcoming letter from the Governor of Texas, the Honorable George W. Bush. They also received the Nimitz plaque.

These survivors represent the largest group of American prisoners to return from Japanese control. As a result they were of particular interest to the

Army and Navy authorities in planning for the return of thousands of other Americans to be liberated from the Japanese. They remained as a group and were

returned to Washington, D.C. Here they received a heroes' welcome and began a period of intensive debriefing on their existence as POWs.15

The Shinyo Maru Survivors Reunion, 7 September 1944 at San Antonio, Texas Booklet has a section entitled STORIES OF THE SURVIVORS. Here

are the details of the trials and tribulations that they endured while prisoners of the Japanese:

I will relate just a few lines of the story about their evacuation by the USS Narwhal, as told by Cletus Overton:

"After being in our bivouac approximately one week, word was received that we were to be at a place on the beach 20 kilometers northward from Sandangan

by 6 p.m. the following day. Early the next morning, we moved out, carrying by litter and Caraboa sleds, the more seriously sick and wounded. We arrived at

the place late that afternoon.

"Colonel McGee informed us that a submarine was expected that night to take as many of us as it had room. One of the 83 survivors had died and Joe Coe,

a radioman, volunteered to stay with the underground forces to help with their communications. I drew number 72. This gave me a small chance of going.

That moonlit evening about 9 p.m., the submarine, US Narwhal, suddenly surfaced some distance from shore. Excitedly, I watched as two crewmembers came

ashore in a rubberized rowboat. As the boat slid upon the sandy beach, one of the two stepped out on one side and asked how many were in the group. Colonel

McGee said, 81. The crewmen flashed a light signal to the submarine. There was an immediate signal back to the crewman who turned and said, we will take

every damn one of you! The other crewman had stepped out on the other side and jammed in the sand a staff holding the American flag! It must have been a

new flag. It seemed as if it were illuminated in the soft breeze and moonlight. The American Flag, the symbol of freedom and liberty! What a glorious sight!

Each of us, by the grace of God, had finally beaten the Japs in our struggles against their tyrannical brutality.

"We were carried by native rowboats and loaded into the submarine, filling every available space. Five days later, we arrived at a military base in

New Guinea. There we were issued shoes, clothes and toilet kits. I'll never forget that good hot soapy bath, shave and haircut. We were fed sumptuously

and slept on good clean beds. The next day, we were moved by torpedo boats to an airbase on another island. We were then flown to Brisbane, Australia and

placed in the 42nd General Hospital on about October 1, 1944.

"Ten days or so later, we boarded the USS Monterey for the United States of America. We had a good but long trip back across the Pacific to

Pier 7 in San Francisco arriving on November 6, 1944, the same Pier from which I had departed November 1, 1941. That was the general election day when

Roosevelt was re-elected to his fourth term and unfinished term as President of the United States.

"Most of the group was sent to Washington, DC for interrogation by the intelligence people. The others were sent to various destinations. We, who went

to Washington, were questioned in minute detail about the treatment received from the Japs and the conditions under which we had lived, as prisoners of

war, particularly the many atrocities they had committed against us. After four or five days in Washington, we were given a 90 day furlough home." 16

Appendices:

Shinyo Maru Survivors Reunion Attendees

Shinyo Maru Survivors

Map of Paddle Attack

Shinyo Maru Survivors Memorial

Gov. George W. Bush letter to Shinyo Maru Survivors

Shinyo Maru Survivors Plaque

"While in her patrol area, about ten miles north of Sindangan Point, Mindanao, she sighted a small convoy. The convoy was made up of a medium tanker,

two medium AK's, two small AK's, two torpedo boats or DE type escorts and one small coastal tanker type craft. There were two planes overhead. The tanker

was a medium sized modern vessel half loaded. The two AK's were new looking ships with two single stack masts, one fairly low stack. ALL VESSELS DID NOT

SHOW ANY UNUSUAL MARKINGS. No identification as to name was attempted because all periscope observations were very brief with flat calm sea prevailing.

Four torpedoes were fired at the tanker with two hits. Two were fired at the leading AK, the boat had to dive deep as the escorts turned toward the boat.

Damage to the tanker and AK could not be seen. However, loud, characteristic, breaking up noises were heard almost immediately and continued on for

sometime after the depth charging started. Commenced taking a total of 45 depth charges and bombs, none close enough to do any major damage, but jarring

the boat considerably. No. 43 was very close. The attack lasted about two hours and then the boat came to periscope depth and started patrolling again."6

"While in her patrol area, about ten miles north of Sindangan Point, Mindanao, she sighted a small convoy. The convoy was made up of a medium tanker,

two medium AK's, two small AK's, two torpedo boats or DE type escorts and one small coastal tanker type craft. There were two planes overhead. The tanker

was a medium sized modern vessel half loaded. The two AK's were new looking ships with two single stack masts, one fairly low stack. ALL VESSELS DID NOT

SHOW ANY UNUSUAL MARKINGS. No identification as to name was attempted because all periscope observations were very brief with flat calm sea prevailing.

Four torpedoes were fired at the tanker with two hits. Two were fired at the leading AK, the boat had to dive deep as the escorts turned toward the boat.

Damage to the tanker and AK could not be seen. However, loud, characteristic, breaking up noises were heard almost immediately and continued on for

sometime after the depth charging started. Commenced taking a total of 45 depth charges and bombs, none close enough to do any major damage, but jarring

the boat considerably. No. 43 was very close. The attack lasted about two hours and then the boat came to periscope depth and started patrolling again."6

Unknown to us, 83 POWs made it to the beach. One died on the beach. "The 83rd man was known as Tennessee. But no one seems know to what his real name was.

He died about two days after we came ashore, and was buried on the hill in back of the town Sindangan."

Unknown to us, 83 POWs made it to the beach. One died on the beach. "The 83rd man was known as Tennessee. But no one seems know to what his real name was.

He died about two days after we came ashore, and was buried on the hill in back of the town Sindangan."